Our ancestors arrogantly believed that they were superior in most respects to other races. So, they had no qualms in the ownership of these people – as slaves – part of our Afrikaner Cultural DNA!

Every year at school, without fail, teachers told us about Jan van Riebeek and the start of the Cape of Good Hope refreshment station in 1652 by the Dutch East India Company -the VOC.

The VOC was a strange ‘beast’ of a company – founded in 1602, the ancestor of modern corporations. This ‘beast’ was the first major corporation. The ‘beast’ was powerful and a law unto itself. It started wars where necessary—tried and imprisoned people and executed and tortured people. No one could stop the VOC. ‘Beast’ it was – oppressive and intimidating. It angered our ancestral Trekboer – all trekking to escape this ‘beast’! The ‘beast’ controlled the market for their hard-earned labour and the price they could get for what they grew.

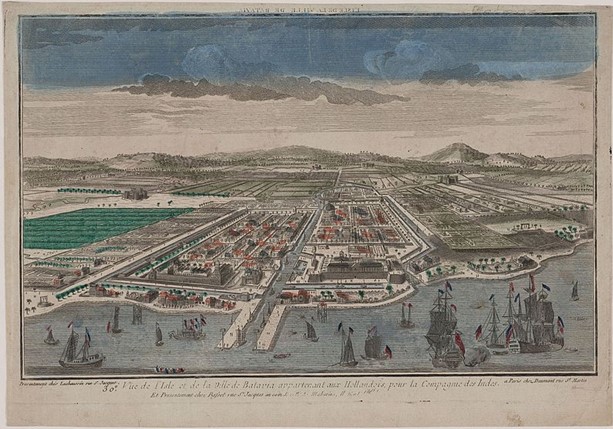

Figure 2: The VOC in Table Bay

Self-serving VOC Commanders ran the refreshment station between 1652 and 1691. Then equally self-serving Governors ran the colony between 1691 and 1795.

There was an even darker side to the activities of the VOC – slavery! Our early family members were slave traders.

Origins

The hub of the VOC slave trade was the walled city of Batavia (Jakarta). From Batavia, the VOC sent slaves everywhere in the known world (Figure 3, Page 11).

Figure 3: A hand-coloured engraving of Jakarta – Batavia created by Jan Van Ryne in 1754

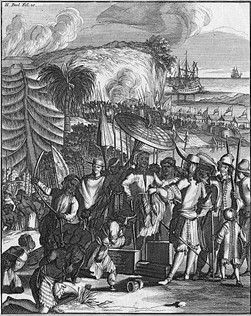

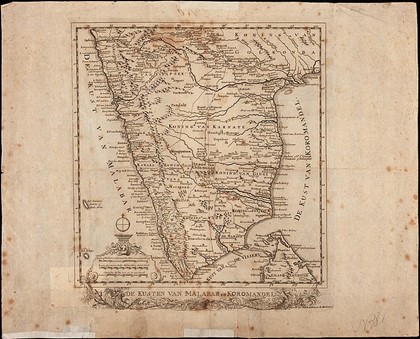

Many slaves came from India – the Coromandel and Malabar Coasts (Figure 5, Page 12) – others from Ceylon and Arakan (Figure 4, Page 11) – next to the Bay of Bengal. Slaves were spoils of war, people captured in raids or people other people wanted to get rid of – then sold to VOC slave traders.

Figure 4: Natives of Arakan sell slaves to the Dutch East India Company at Pipely/Baliapal (in Orissa) – 1663

Figure 5: The Malabar and Coramandal Coasts – a VOC Map

Jan van Riebeeck, the Commander, decided they needed slave labour to do the hard and dirty farm work to keep them alive, just after arriving at the new refreshment station in 1652. The Khoikhoi disdainfully refused to work for the very low wages – to do the back-breaking work under hard taskmasters.

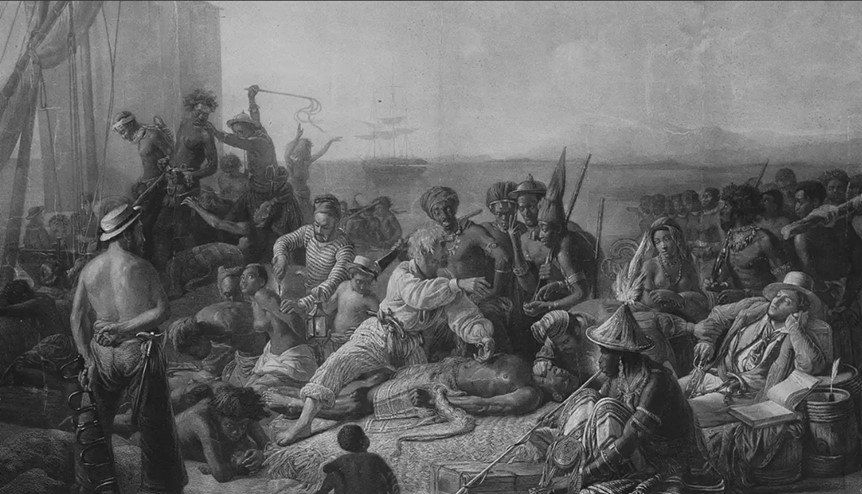

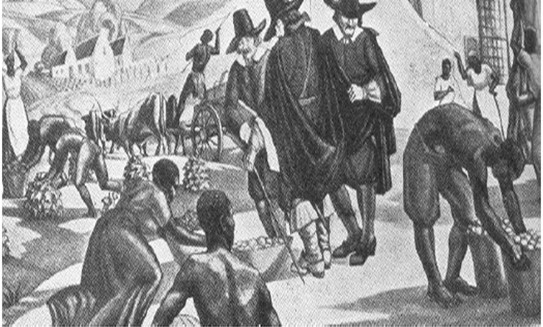

The slaves had to be strong for that type of work. The slaves from Madagascar were the most popular – ‘strong and healthy’. Eventually, two-thirds of these hapless people came from Madagascar – some 4000 over 150 years. All at the Cape were willing and eager to profit from this human misery (Figure 6, Page 12)!

Figure 6: Trading in Misery – Chicago History Museum

A major player was the King of Antogil – Madagascar. Constantly fighting he took many prisoners of war. There was a good market for them. The Dutch, Portuguese, English and French slave traders waited patiently for them. They traded muskets guns and powder and trinkets for these chained ‘products’. The king, and then the other kings demanded more and more weapons and other goods for these cargoes of misery.

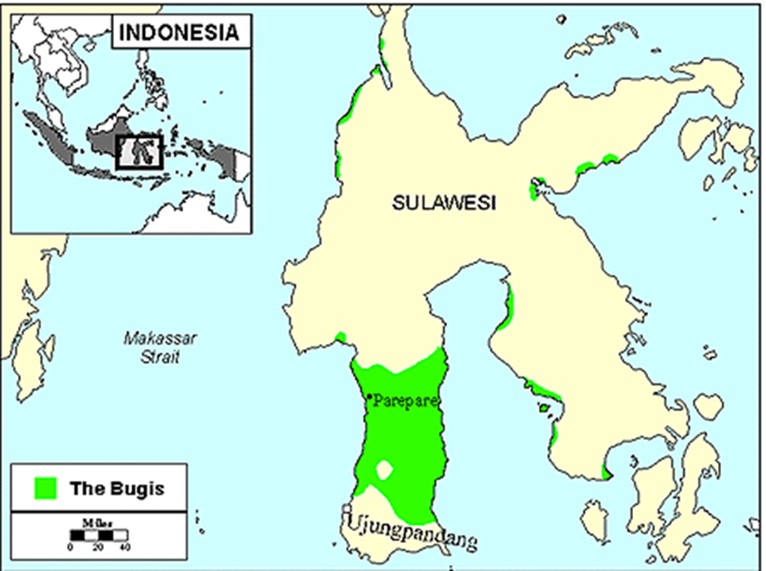

Slaves came to the Cape from anywhere in the VOC world. Cape demographics today show that many slaves came from Macassar and the Buginese region in Sulawesi (Indonesia) (Figure 7, Page 13). They also worked the farms but also brought culture and skills with them. Their handiwork is still evident at the Cape today.

The Buginese (Bugis) (Figure 7, Page 13) brought a distinct culture with them. Buginese DNA – fused with European DNA, is evident in our Afrikaner families.

The Bugis were, and still are, dynamic, self–sufficient and deeply religious people. They were conscious of honour, status and rank – but also dangerously ready to take offence. The Buginese men had a bad reputation at the Cape, banned by the VOC in 1767 due to their ‘murderous nature’. This ban was immediately rescinded. The women had something to do with it, as the VOC men loved the Buginese women – they were not prepared to forgo one of the most popular recreations in that tough environment – getting rid of the women who were the ‘best in bed’.

Figure 7: Ujungpandang (Macassar) and Buginese Region

The great success of wheat farming and viticulture in the Cape was due to the slaves. Pastoralists and livestock farmers survived and flourished on the backs of the slaves. My Smit, Venter, Potgieter, Mouton families, and Dedries’s Beukes, Visser and Breytenbach families benefitted greatly from their slaves – their key asset.

The VOC paid badly – most employees were allowed to ‘moonlight’ – provided there was no conflict of interest. If there was a problem – there were floggings, working in a chain gang, or an appointment with a torturer! The rewards and money they received for this business, on the side, were called ‘morshandel’ (leftover trading) – so they dabbled in the slave trade. Many grew very, very wealthy from ‘morshandel’.

There is no evidence that our families grew rich from ‘morshandel’ – but they may have!

The VOC paid lip service to their treatment of the slaves – they were supposed to treat slaves ‘well and kindly’; feed and clothe them properly and protect them from the weather. The contract stated that they should treat slaves so that the slaves were well disposed to them. They were to teach them trades and make good farmers out of them. That did not happen!

Figure 8: Vryburghers Supervising Slaves in the Cape

The VOC managed the slave trade with an ‘iron hand!’ Slaves kept fleeing, trekking into the interior together with deserting VOC employees. They all wanted to get away from the VOC as quickly as they could!

The Managers

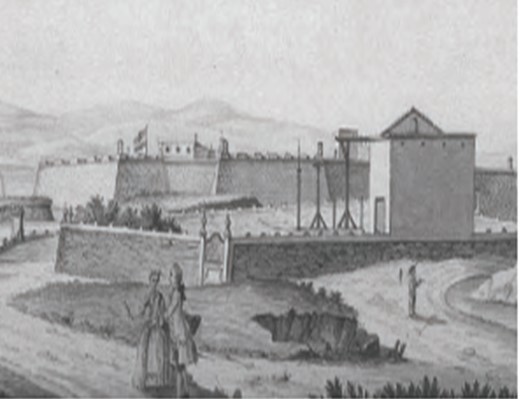

The law was not on the side of slaves and deserters. Punishments were bizarre and cruel. The gallows and torture racks at the Cape were notorious – featuring prominently at the Cape Town Castle – as Thomas Rach showed (Figure 9, Page 15). He was a gifted artist in the Danish court and a topographical artist in Haarlem in the Netherlands, who landed ‘unexpectedly’ at the Cape. He was a VOC gunner in the artillery – probably fleeing some scandal, debt or criminal act.

When he arrived at the Cape in 1762, the conspicuous gallows at the castle. terrified him. Maybe he thought that his past may catch up with him. The sign at the gallows left such an indelible impression that he made a painting of it. It said: ‘Heus Viator!’ (Hail Traveller). Visitors immediately knew that they could pay the ultimate price for criminal behaviour – even for stepping out of line.

Slave owners punished slaves for the slightest misdemeanours. The most common punishment for the lower-scale infringements was to be sent to work in chains on Robben Island. Many died there – worked to death. Gruesome punishment was necessary to deter other slaves from committing ‘copycat’ offences.

Figure 9: The Gallows at the Castle

The slaves owned by our ancestral families living in rural areas had the worst treatment. They worked the grain and livestock farms and the vineyards – the wheat farms and vineyards next to each other in most areas. Slaves were moved from farm to farm to cover peak periods during harvesting. On these farms, they were repeatedly sjambokked (flogged) every day and worked until they dropped from exhaustion. The sjambokking increased in intensity during bad times.

Slaves that did not die from the sjambokking were often sold as shepherds – broken in body and spirit! Minor offences such as losing sight of cattle or not sweeping the floor properly could result in a brutal sjambokking. A slave could lose his or her life for such a simple thing. Sometimes, more than one person used the sjambok – it could be a team effort.

The VOC encouraged this – punish all mistakes to prevent things from getting out of hand! The VOC archives contain records of unimaginably brutal punishments meted out to slaves.

Lady Anne Barnard sketched the government’s hangman (Figure 10, Page 16) a ‘caffer’, who did the Cape Colony’s dirty work. Such a ‘caffer’ was usually a slave origin or freed slave – ‘vrij swarten’ (free blacks). They were employed as ‘assistant executioners’ or ‘chief executioners’ – paid handsomely for the execution of their duties!

Figure 10: The Executioner

VOC archives contain a detailed record of these duties. Lower-end duties were breaking limbs; chopping off hands; random torture; tearing off flesh with red-hot thongs; burning anywhere on the body; scourging and branding anywhere on the body. Higher-end duties were decapitation, hanging and strangling.

Sentences handed out, specified in the greatest of detail what had to be done to the person. Torturers were well-trained, efficient and at times innovative in carrying out their duties!

A famous case was that of my fifth great-aunt, Maria Mouton. Maria and a slave, Titus van Bengale were lovers. She killed her husband Franz Joosten on 3 January 1714, aided by her lover, Titus van Bengale and the slave Fortuin of Angola. They buried his body down a warthog burrow. His murder was exposed when animals later dug up the body.

They were all tortured to extract confessions before being gruesomely executed.

I will tell Maria’s story later.

Details of the slaves owned by our ancestors are given in Appendix 3: Details of Slaves Owned, Page 207.

Slaves were treated as property, and property only – a cause of great suffering and ignominy to most. There is the sad trial of Cupido van Malabar [1] in 1739 – the slave of my ancestor Erasmus and his wife Cornelia van Emmenes –a young married couple at the time.

Cupido worked on their Drakenstein farm where he attempted to kill Cornelia. At his trial, he told how he had threatened Cornelia and her child with a knife and how he had said that he would kill himself. Slavery had taken away his desire to live!

He told the Landdrost (magistrate) how much he resented the endless back-breaking work, no freedom at all, the type of clothes he had to wear and the lack of women in his life – he tearfully told the Landdrost that he longed for freedom, that which he had in Malabar. He hung his head as he said that his master owned everything he had, also his life. The only way forward and to be free was to flee this life – kill himself. That would deprive his master of his ownership!

The court was told how Cupido crazily wielded a knife, threatening to kill everyone in the family. He lunged at Cornelia, who jumped back to avoid the desperate half-crazed man. But, before he could do any harm to her or her child, he was disarmed before he could do any harm.

There was no mercy for Cupido. The sentence of the court, read out by the Landdrost was: ‘to be handed over to the executioner and to be tied on to a cross, to be broken alive from the bottom, without the coup de grace, to remain lying thus on the cross until he has given up the ghost; thereafter the dead body to be dragged to the outer place of execution, to be placed upon a wheel and to remain lying on this until being consumed by the air and the birds of heaven’[1].

The San

Slavery was rife during the VOC and Trekboer wars against the San. The men were killed, and the women and children taken as slaves were prisoners of war and their families.

There is the record of Dedrie’s great–great grandfather, Floris Brand who had a San child Klaas Bosjesman given to him, by his captative father. His mother was killed in one of the raids on the San. Floris undertook to ‘look after’ him until he reached maturity. But Klaas was treated as a slave in the household and punished severely for frequently running away. He was caught on one occasion and appeared in front of the magistrate in Kenhardt. Klaas complained to the magistrate that he had run away because of the beatings he received. When asked about this, Floris said: ‘I punish my children when they do wrong’. There are many magistrate records of San slave children being treated with unspeakable cruelty!

Step forward about 200 years to the days of the Kruger-led South African Republic (ZAR). Had our ancestors become less despotic and cruel when it came to punishing slaves or the Black population?

No!

During the 1860s, the Kgafela‐Kgatla tribe lived on Oom (Uncle) Paul Kruger’s farm, Saulspoort, in the Western ZAR. I can call him Oom Paul, as older generation Afrikaners do to this day – also, he was a distant cousin! These tribe members were a more modern version of the Cape slaves – unpaid labourers living on his farm and compelled to work for the Boers.

Oom Paul and the local Boers wanted to build dams in the area to irrigate the lands. They forced these tribesmen to pull cartloads of stone to the construction site. The tribe people refused and rebelled. Oom Paul then publicly and humiliatingly flogged their chief Kgamanyane in front of everyone assembled – the tribespeople and armed Boers. The tribe left as one – migrating to present‐day Botswana.

My Oupa (Grandfather) Chris Smit, a descendant of Erasmus, and Uncle Thys Venter regularly flogged labourers on our ancestral farm Alexander. This practice they learned from their parents – passed down through the generations. As a child, I witnessed such floggings on the farm.

The first period of slavery, under the VOC, lasted from 1652 to about 1795. A second period of slavery lasted from 1808 into modern times in South Africa. The country was oddly empty when our Voortrekker family trekked into the interior in the 1830s. They claimed they entered a wasteland, a country devastated by a ‘genocide’. A veritable ‘terra nullius’ – just there to be taken! At school, we learned that the ‘Mfecane’ or ‘crushing’ was responsible for this – a genocidal event of black-on-black destruction involving the war-mongering Shaka, king of the Zulus.

The ‘Inboekstelsel’ (‘Booking System’)

Afrikaners, including our families, continued to use slave labour into the days of the ZAR[2]. The government brought in a system called the ‘inboekstelsel’ (booking system)– a system of indentured child labour.

The Sand River Convention signed in 1852 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland formally recognised the independence of the Boers north of the Vaal River. There our Transvaal families said no to slavery north of the Vaal River. But it never stopped – it continued with slave-raiding on the Transvaal border and widespread use of the ‘inboekstelsel’ until 1870.

The ‘inboekstelsel’ itself was slavery – according to ‘Rainbow Nation’ historians. Indentured children were captured during raids on the local tribes or handed over as apprentices by their parents in return for land or goods. These child slaves were very valuable – known as ‘black ivory’! I would not be surprised if my grandfathers and great-grandfathers benefitted from this system. Many farms had Bantu people living on their land even in our time – unpaid workers farming the land – in return for food and a ‘stroois’ (straw hut). If they left, there were serious consequences – they became ‘vagrants’ who had to be hunted down and brought back – often to receive a lashing.

Western ZAR Boers[3] obtained women and children as slaves and used them as domestic servants and plantation workers. Slave raids took place regularly, with thousands captured, traded, and used for labour throughout the ZAR.

How is this known – nobody took notes! We know this by the stories told by descendants of those slaves. ZAR officials, including President Martinus Pretorius and Commandant-General Paul Kruger, also told about the raids and everyone knew that they owned slaves – it was part of an official policy – slaves were needed.

The Mfecane

Nowadays, ‘Rainbow Nation’ historians are split on why the country was so empty! A new, sinister theory has emerged. Missionaries, Griquas, Bantu Tribes, the Voortrekkers and British colonists and traders were all involved in the lucrative slave trade.

There were many conflicts between pastoral tribes, vying for grazing and trading territory before our Voortrekker ancestors entered their ‘shangri-la’. Slavery was rife. Victors sold many thousands of black women and children to slavers. Smaller tribes fled when rumours spread about the ships waiting in Delagoa Bay – to upload as many slaves as they could accommodate!

The slave trade at Delagoa Bay also expanded from about 1810 in response to demands for labour from plantations in Brazil and on the Mascarene Islands. Just before the Voortrekkers arrived, the slave trade in Delagoa Bay boomed again – thousands of slaves boarding the slave ships in chains, clanking as they disappeared down into the hulls, ready to be put to work in the plantations of Brazil.

Infamous were the people in the Gaza kingdom established in the highlands of the middle Sabi River in Mozambique in the 1830s by Soshangane, the Ndwandwe general. He was driven out of Zululand by Shaka during the Zulu-Nguni wars known as the Mfecane.

Soshangane ruled the area between the Komati and the Zambezi rivers with an iron hand, integrating the local Tsonga and Shona peoples into a Zulu-type nation – Gazaland. The Portuguese kept a low profile – they were no match for Soshangane – only happy to trade with the people from Gazaland – trade in slaves! The Portuguese used the Gaza, Ngoni[4], and anyone else as foster slavers who joined the Portuguese soldiers in inland raiding.

Along the Limpopo and Vaal River links, the Shangaans competed with Griqua slavers in supplying the Cape. Slavers burned crops. There was famine everywhere. Communities and tribes, such as the Ngwane, Ndebele, and some Hlubi—fled westward into the Highveld mountains during the 1810s and 1820s.

The Missionaries, Griquas and Zulus

The missionaries were involved – sincere and misguided ‘men of God’. They led a Griqua raid on the ‘Mantatees’ (Southern Sotho tribe) people at Dithakong in the Northern Cape in 1823. The Griquas sold those hapless survivors to Cape farmer settlers, as they had done during the Xhosa-British wars of 1811-20. There were no qualms – market forces dictated where the slaves could be sold most profitably. Farmers were desperate for this slave labour – men, women and children. They were willing to pay a lot for these human machines.

Swazi people from Ngwane (Swaziland) fled from the UmMzinyathi (a Zulu sub-tribe) inland to the Caledon River. Before long, the Griquas turned up and rounded up the non-disabled people, which they sold as slaves into the good Cape Colony market. The Griquas attacked the wretched Ngwane and sold them as slaves to the British army seeking ‘free’ labour in 1828.

In Natal, Henry Fynn, a so-called ‘trader’, had a private army of 2000 African mercenaries, which he used for ivory-hunting, to support Shaka and to capture slaves to sell to American and Brazilian slavers waiting in Delagoa Bay. Fynn’s mercenaries were known as the iziNikumbi (locusts) – one can only guess why?

So, the country became empty!

Slave Ownership

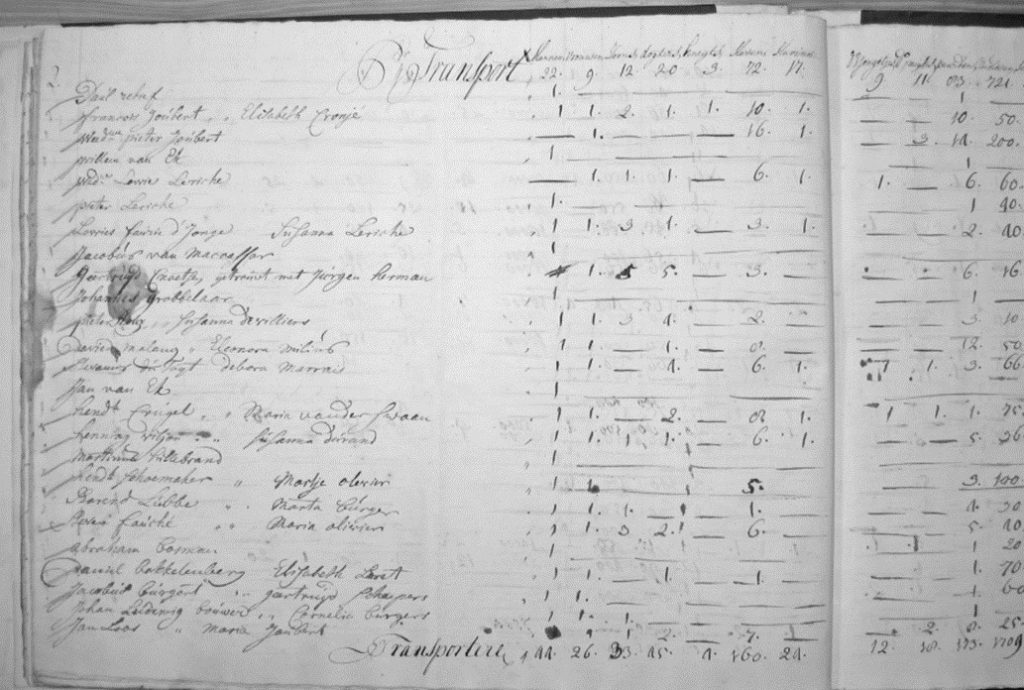

My 6th generation great-grandfather, Daniel Bockelnberg and his wife Elizabeth Loret, my 6th generation great-grandmother – a Huguenot ancestor, had the names of their slaves, the names of their overseer (knegt) servant, slaves, livestock, horses, crops and weapons they possessed recorded once a year in the ‘opgaaf’ (registry) by local VOC officials.

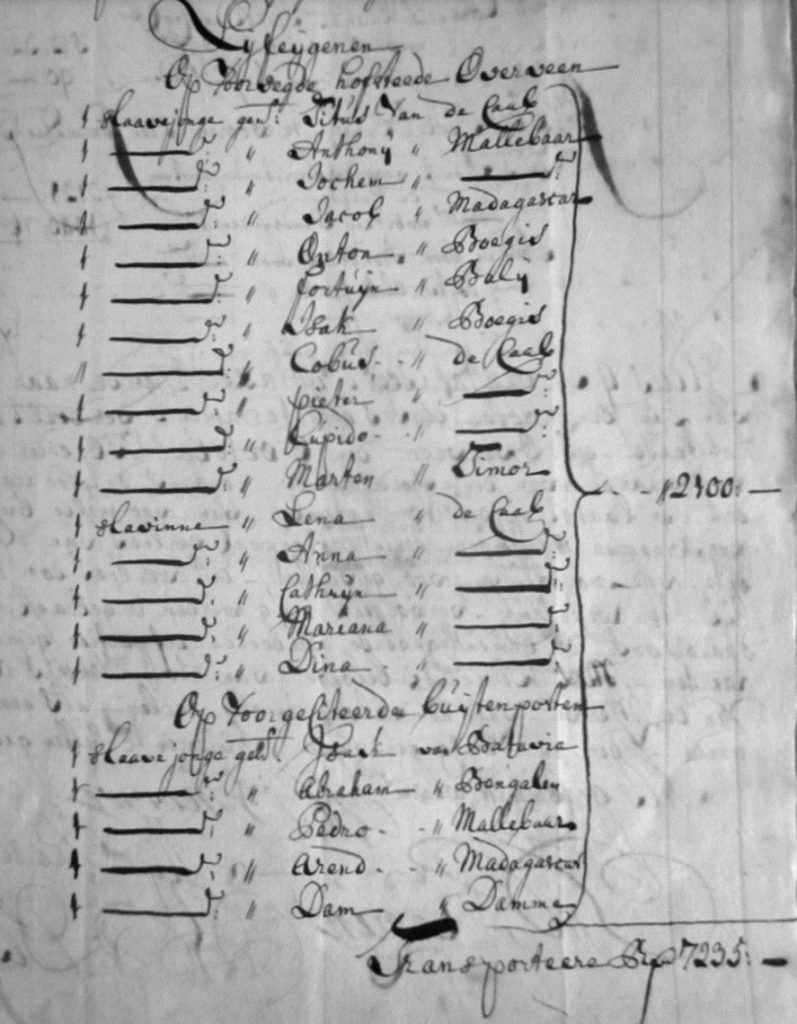

An extract of their ‘opgaaf’ for the year 1737, from the Cape Archives, for their farm in Stellenbosch – is shown below.

Figure 111: Slave Estate Inventories

Aletta Keyser, my 5th generation great aunt (Figure 92, Page 195) owned slaves from many destinations, Malabar, Sulawesi (Bugis), Madagascar, Timor, Batavia and those locally born – ‘van de Caab’ (from the Cape).

My Smit family ancestor, Erasmus[1] Smit, owned, bought, and sold slaves. In 1727 he sold the slave Aaron from Bali to Jacob Heijden for 110 Rixdalers (approx. £25 Sterling). In 1728 he sold another slave from Bali to Jan Mulder for 100 Rixdalers (approx. £23 Sterling); he bought Caesar, a slave from Ceylon, from Matthijs Kruger for 40 Rixdalers (approx. £9 Sterling) in 1731. In the slave census of 1760, it is recorded that he owned fifteen slaves and two freed slaves. these included Cupido van Malabar, Joumat van Bugis and September van Bugis.

Erasmus’s slaves were his property like his farm and livestock – they were a capital investment and his most valuable indispensable asset. The maintenance of his slaves was costly and a risky investment for him – which put a huge strain on their finances – but he used them as security to borrow money. My ancestral great grandfathers, following Erasmus, Pieter and Gerrit, inherited Erasmus’s slaves and bought some of their own. When the slaves in the colony were emancipated in 1834 by the British government, Gerrit lost a lot of money – he did not receive compensation for his slaves – one of the reasons he decided to join the Great Trek into the interior.

My ancestral great-grandfather, Pieter Venter[2] also owned, bought, and sold slaves. He farmed at ‘Weltevreeden’ near Piketberg. In 1723 he bought the slave Februarij from Indonesia from Paulus Artois for 60 Rixdalers (approx. £13 Sterling). The same year, he bought the slave Cornelis van Bengal from Johannes Kemp for 85 Rixdalers (approx. £19 Sterling). The slave census of 1760 records that he owned four slaves and two freed slaves. Dedrie’s ancestral great-grandfather, Dirk Beukes, owned, bought, and sold slaves. The slave census of 1782 records that he owned six slaves and two freed slaves.

[1] My 4th generation great-grandfather – Figure 54: My Smit Family Tree, Page 194.

[2] Figure 55: My Venter Family Tree, Page 194.

[1] Worden and Groenewald – Trials of Slavery: Selected Documents Concerning Slaves from the Criminal Records of the Council of Justice at the Cape of Good Hope, 1705–1794.

[2] South African Republic.

[3] Slave-raiding and Slavery in the Western Transvaal after the Sand River Convention; Fred Morton; Loras College; Iowa.

[4] An ethnic group living in Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia, in east-central Africa. The Ngoni trace their origins to the Zulu people. The displacement of the Ngoni people in the great scattering following the Zulu wars had repercussions in social reorganization as far north as Malawi and Zambia.