One branch of my matriarchal family tree leads to the French Huguenot ship’s surgeon, Jean Prieur du Plessis.

The Cape became a refuge for French Huguenots who fled religious persecution in Europe in the latter part of the 17th Century. As a result, many of our ancestors were Huguenots, such as my 7th-generation great-grandfather, Jean Prieur Du Plessis.

The family tree shows Jean Prieur is my 7th great-grandfather.

Jean was born in Poitiers, Poitou-Charentes, France in 1638. He came to the Cape from Europe after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 – a pivotal moment in our family’s history.

The Edict of Nantes, drawn up at Nantes in Brittany in 1598 by King Henry IV of France, gave religious freedom to Jean and his fellow Huguenot Protestants after a long period of religious strife between Catholics and Protestants.

A key player was ‘Good King Henry’ who converted to Catholicism at this critical juncture – a highly political move – encouraged by his mistress – like Eve in the Garden of Eden!

‘Good King Henry’ was born and baptised a Catholic but raised a Huguenot, like Jean. So he had to fight against the Catholic League, which wanted the throne to be Catholic – and, as they believed, to stamp out ‘satanic’, evil Protestantism in France. Besides, they wanted the Duke of Guise to occupy the throne.

‘Good King Henry’ cleverly held onto the throne by becoming Catholic again. But people did not call him the ‘good king’ for nothing. He was rational and tolerant, willing to ‘live and let live’ – so he signed the Edict of Nantes. At last, the Protestants had religious freedom and an end to the dreadful religious wars that had raged for more than 30 years. Jean Prieur was free to worship in public after a very long time. He could not work or live in Paris, but his quality of life improved enormously; he had full civil rights and access to employment.

But it was not to last for that long!

The Huguenots remained deeply suspicious of the Catholics. The Catholics remained uneasy about the heretics they had to mingle with

Jean Prieur was terrified that there would be another St. Bartholomew Massacre. On the night of August 1572, during Henry IV’s wedding, Catholic vigilantes killed eight thousand Huguenots! Thousands of Huguenots had come to celebrate his wedding. But his grandmother, Catherine de Medici, hated the Huguenots. She persuaded her son Charles IX to kill them – she was the driving force in the war against them. She died before ‘The Good King’ signed the Edict in 1598.

Unfortunately, ‘The Good King’ was murdered in Paris on 14 May 1610 by a Catholic fanatic, François Ravaillac, who stabbed him in the Rue de la Ferronnerie.

The Catholics eroded the work done by ‘The Good King’. Cardinal Richelieu began a siege of the free Huguenot cities. La Rochelle, the last free city, fell in 1629.

A tragic and ironic twist of fate – Jean was related to Cardinal Armand Jean du Plessis, the ‘Red Eminence’ – the foreign secretary of France.

The Cardinal and his wife were Protestant haters – haters of the heretics. So King Louis XIV, ‘The Sun King’ – grandson of ‘The Good King’, with the support of Cardinal Richelieu and Pope Clement VIII, revoked the political and military acts in the Edict in 1629.

The ‘die was cast’ for the Huguenots!

Persecutions spread throughout the country and reached a crescendo in 1685. Finally, the Pope and ‘The Sun King’ revoked the Edict – declaring ‘one faith, one law, and one King’.

It was a disaster for my ancestor Jean – depriving him of all his hard-won religious and civil liberties.

Jean did not relish the idea of being burned at the stake! Huguenot churches and homes went up in flames in front of their eyes. Huguenots screamed and writhed in agony as the flames finally silenced them at the stake in the village squares.

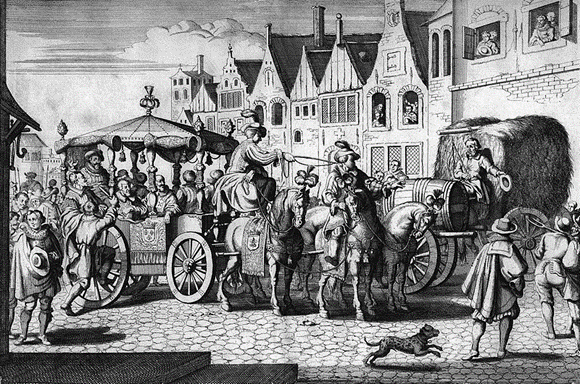

Jean joined the exodus, fleeing with 400,000 or more Huguenots, going to Switzerland, Germany, England, America, and the growing Cape Colony.

Then he fled to the Antilles, where he met and married Marie (Madeleine) Mentanteau in June 1687, my 7th generation great-grandmother in St Thomas in the US Virgin Islands. She fled to St Thomas from Poitiers, born there in 1665.

Like many Huguenots, Jean and Marie moved back to Amsterdam, where they joined Amsterdam’s Waalse (Walloon) Church.

Jean and Marie knew they would be safe in Holland. The Dutch Reformed Church and the Huguenot Protestants followed John Calvin’s theology and shared Jean and Marie’s hostility to ‘The ‘Sun King’ – who believed he had absolute and divine power!

On 8 Jan 1688, Jean swore allegiance to the VOC in Middelburg, Zeeland, to move to the Cape as a Vryburgher. Jean and Marie sailed on the Oosterland on 29 Jan 1688 and arrived in the Cape on 26 Apr 1688.

Jean practised as a medical doctor in Stellenbosch and Drakenstein.

He tried to save the life of one of my eighth-generation great-grandfathers, Abraham Bastiaansz Pyl – that story I will tell in a later chapter! We carry with us many good and bad attributes of our Huguenot ancestors!