There is ‘No Other’

The Clare Valley wine region, Flinders Ranges, Wilpena Creek, Parachilna Gorge, Oodnadatta Track, Coober Pedy, Breakaways and the Arid Lands Botanic Gardens beckoned hundreds of kilometres away—unique, foreboding, yet lovely—there is ‘no other’ Outback!

We set out enthusiastically from Melbourne to Adelaide to embark on the Gekko tour to the outback. Little did we expect that we would nearly succumb to the cold as one of the strongest cold fronts swept across the south of the country. We had seen the ABC programme on the mass migration of birds to the lake, feeding on the shrimps that crept out of the salt-coated shores. We could not wait to skim over the shores of the lake and to see the Macumba Creek inlet.

Drive to Adelaide

We travelled to Ararat, Stawell and Horseham after leaving Melbourne at 2 pm. We couldn’t believe how green the countryside had become after the devastating drought in Western Victoria.

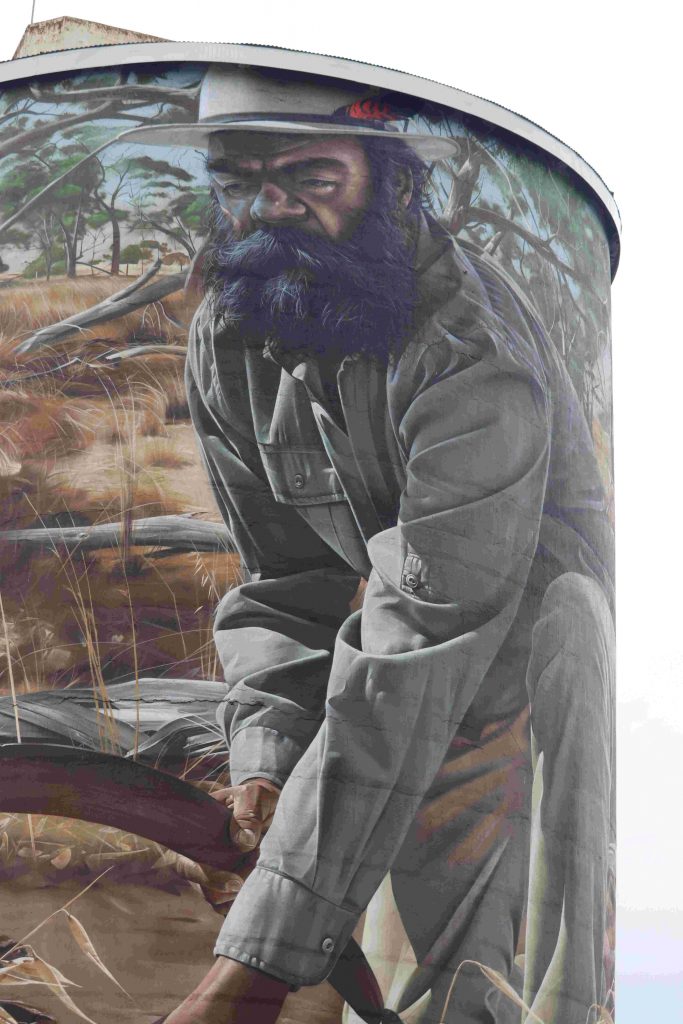

The street and silo art in Horseham is an experience not to be missed—unsurpassable—breathtakingly realistic!

Coonalpyn

The silo and mural art in Coonalpyn were as spectacular as that in Horseham; a delightful hour with a coffee break will dispel any travel weariness!

Hahndorf

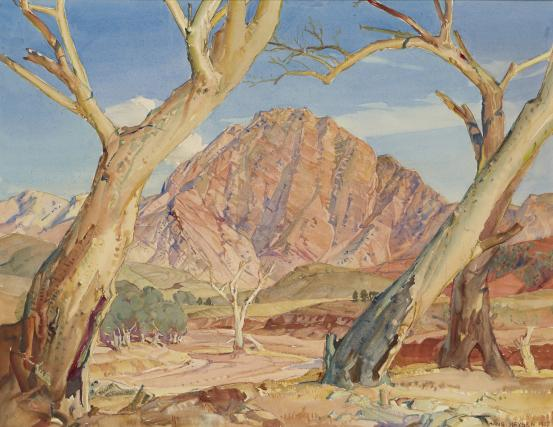

After many hours of hugging the asphalt, skimming the beautiful, sculptured countryside, admiring the wattles showing their gold and the modest eucalypts showing their spring flowers, we reached Hahndorf, a small town in the Adelaide Hills. Our European DNA delighted in the town settled by 19th-century Lutheran migrants and the original German-style architecture and food. We learned that this was the stamping ground of the German-born landscape painter Sir Hans Heysen.

We were excited that we were going to travel into the outback to see what inspired Hans Heysen.

Seven Hills Winery

We spent two nights at the Alba Hotel in Adelaide before setting off the next morning to the Seven Hills Winery in the Clare Valley.

We were to be picked up at 7.00 am on the morning of our departure by ‘Xavier’, our tour guide, an experienced guide with some 35 years of driving up to the lake and beyond. We were unsure about his name being ‘Xavier’, but time would prove that we were mistaken about his name.

But he had a very long drive ahead of him and a strict schedule to meet, so he expected good herding behaviour! Dedrie and I were the first to draw his ire. I was sure that I had packed our fruit and sandwiches in my rucksack. Dedrie was packed and ready to go at 6:45. She asked me to make sure our snacks had been packed. With time running short, I began searching through all my luggage. ‘I can’t find the snacks!’ I shouted. Dedrie finished her final packing and began searching as well. Everything in the room was turned upside down. Panic and inefficiency set in. I rushed down to the car, parked in the hotel garage for the period we were to be away. ‘Nothing there!’ I shouted as I swung the room door open. The time had crept up to 6:57. In desperation, I upended the rucksack. There the snacks were—neatly hugging the lower recesses of the bag. ‘I have it, ‘ I shouted and sprinted downstairs to the foyer with Dedrie shouting behind me that she will be down, ‘In five!’

The coach was packed with ‘Xavier’ pacing up and down and staring up and down the road in front of the hotel. Everyone had claimed their seats on the coach. ‘Xavier’ mumbled agitatedly, ‘There are two missing—still two missing’, he growled.

Dedrie turned up at 7:10, as ‘Xavier’ paced up and down, circling the coach like a wounded bull. She dragged her luggage at breakneck speed through the foyer and outside to the bus. ‘Xavier’ was steaming. ‘There is still someone missing,’ he shouted. Someone shouted back that the missing person was waiting at Seven Hills. ‘Xavier’ did not take lightly to this state of affairs and took his seat, switched on the radio, with ‘Gone Gone Gone’ by David Blasucci, blaring into the passenger section of the coach.

We set off in the pouring rain with our morose tour leader. We all agreed amongst ourselves that ‘Xavier’, who had not introduced himself, had probably ‘got out of the wrong side of the bed’. Dedrie apologised to the rest of the group and a grumpy ‘Xavier’ that I was the cause of the belated departure. It would take at least half a day before the atmosphere thawed and we all became better tour mates.

Another reason for the chilly atmosphere on the coach was that one of the members, sitting next to the window, had water trickling down his neck from an unsealed leak in the roof. ‘Xavier’ had to stop the bus, get out and attend to the leak in the pouring rain.

Dedrie asked the guide, ‘Xavier’, about halfway to the winery, ‘Xavier, are we nearly there?’ I’m actually Paul, ‘Xavier’ said. We all agreed, that Paul should have at least introduced himself when we set out—’Tour Guide Theory–101!’

But Paul would vindicate himself as the tour progressed. He would prove to be a no-nonsense, walking encyclopedia kind of guy who could rattle off dates and facts about the Outback without a break in his train of thought. At certain junctures, it was story time. His stories were rich and imaginative—never boring. Some stories did not gel with the historical narratives or Wikipedia; there was a semblance of truth in everything, though.

Looking back, I would recommend him as a tour guide, interesting and informative. His driving skills were top-notch, given the very tight schedule we had. He could improve on his departure mood skills, but, then again, who would not be morose when waiting for people to board a bus in the most trying of conditions, and in the most inclement weather?

His pride and joy was the very tour bus we were travelling in, which he had built himself. He told us that he built classic cars, specialising in the 1950s Chrysler (I recall). These skills were used to build the tour bus, so we believed we were in good hands.

Seven Hills Winery

Paul’s level of verbosity increased somewhat as we headed north to the Clare Valley, renowned for its excellent wines, with some time to visit the Seven Hill grounds, the oldest winery in the region, established by the Jesuits in 1851.

When we arrived at the Seven Hills Winery, we stepped off the bus into bitterly cold weather— inadequately dressed for the occasion. It was the first time in 40 years of living in Australia that my teeth chattered. The last time that happened was on my way to school in Winter on frosty mornings in the Transvaal Highveld.

We entered the St. Aloysius Church, followed by a desperate visit to the toilet and then to the crypt. Still, we had enough time to appreciate the beautiful church interior and the conservatively hung paintings along the walls.

We visited the crypt; this is the resting place for Sevenhill’s most notable Jesuits. Paul pointed out that this was the only parish church in Australia with a crypt; this final resting place for Jesuits is a historical treasure. The names that are carved into the slate and marble headstones that line the vault refer to the Jesuits who significantly contributed to the development of Sevenhill and its missions from 1851, when the property was settled.

From 1851, 42 Jesuits were interred in the Saint Aloysius crypt. The first to be placed there was Brother George Sadler, who died in 1865, aged 51, when he was hit by a flying fragment of rock while quarrying the property to obtain stone for the building of the Church.

Other notable burials are Brother Schreiner, aged 79, the first of the seven Jesuit winemakers, Brothers Lenz, Storey, Hanlon, and John May.

Laura

A coffee and toilet stop at Laura was the next stop. The cold proved to be all-pervading. The draft through the coach door chilled us to the bone. We found a local store and coffee shop, where we huddled next to the most remarkable Diesel heater. I struggled to get Dedrie away from the heater where she was trying to warm her numbed hands. She got into a discussion with the owner, who described the design of the novel heater in detail to her.

Stepping outside, we saw the statue of C J Dennis—’ the laureate of the larrikin,’ who popularised Australian slang in literature and who wrote: ‘The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke’, such as the song below:

An’ ev’ry song I ’ear the thrushes sing

That everlastin’ message seems to bring;

An’ ev’ry wind that whispers in the trees

Gives me the tip there ain’t no joys like these:Livin’ an’ lovin’; wand’rin’ on yer way;

Excerpt: ‘The songs of a sentimental bloke

Reapin’ the ’arvest of a kind deed done;

An’ watchin’, in the sundown of yer day,

Yerself again, grown nobler in yer son.

C.J. Dennis towers four metres over the lawned median strip in the Laura CBD.

Created by Adelaide artist Dave Griffiths, the steel and copper structure is of Dennis holding a pipe and reading a book of his verse. The detail in the sculpture is amazing, given the materials used. The statue stands as if C. J. Dennis is reading, pondering and recalling ‘Of the long-gone Laura days’.

LAURA DAYS

From: laura days

Dreaming to-day in a forest green

Where the great gums rake the sky,

My thoughts turn back to another scene

And to old days, long gone by;

To a land of youth, and a youth’s employ,

And – to filch another’s phrase –

To the men who were boys, when I was a boy,

In the long gone Laura days.

Silo Art—Wirraburra

Paul became enthusiastic about the Viterra Silo art in Wirrabara. Smug, the silo artist, worked wonders on the 28-meter-high canvas.

Sam Bates (SMUG) , a self-taught artist from Australia, is known for his photo-realistic murals worldwide. His skills evolved from early rebellious spray-painting and now grace buildings globally, including the Wirrabara silos.

https://www.australiansiloarttrail.com/nullawil

He worked nonstop over a period of three weeks to complete the stunning artwork. Smug converts the simple silo buildings into veritable masterpieces rising out of the landscape, beckoning to tourists to extricate cameras and phones for pictures from all angles.

Smug employs a boom lift to work at those great heights. Using precise strokes and meticulous geometry across the massive surface area of the silos, he gives vibrant life to his subjects.

Melrose

We then travelled to Melrose, a lovely little town nestled in the foothills of the Flinders Ranges. On the way, the sun filtered through and lit up the yellow canola fields with Mount Remarkable in the background. Our eyes followed Paul, our laconic guide’s hand, as he mumbled, ‘Mount Remarkable.’ We were travelling too fast past yellow field after yellow field to take any decent photos.

We had to guess that the fields were Canola! Paul had obviously seen enough of yellow Canola fields to dissuade him from addressing our agricultural enquiries. We did hear someone from the back exclaim, ‘What are these beautiful yellow fields, Paul?’ Someone countered, ‘Ask Mr. Google!’

The bus passed through the delightful countryside—too quickly for all on the coach. Photos taken from the coach captured dry riverbeds and creeks heralding our approach to the ‘arid lands’. We were itching to get out of the coach to absorb the atmosphere and experience the arid land flora and fauna.

Quorn

Driving further north, we arrived at Quorn for lunch at the Quandong Cafe. The bitterly cold wind had subsided, but the rain still fell in patches. The Quandong Cafe has become an institution of food and coffee within Quorn since 1995.

The lunch was very good, a home-made quiche and salad—served in ‘old school’ South Australian style. After lunch, we made it back to the coach parked near the Railway Station—the junction of the Sydney-Perth and Adelaide-Darwin railway systems in 1917. Dedrie bought a beautiful locally handmade silk scarf.

The railway lines featured wherever we went. There are numerous semi-successful or partially unsuccessful rail projects in South Australia. Mining, water, vast distances and incompetent colonial government officials with grandiose, impractical ideas were the responsible drivers for these projects. One of these was the Pichi Richi Railway. The details of its inception and final demise are as follows—from Wikipedia.

Imagine the rugged beauty of the Flinders Ranges, where the relentless sun casts a warm glow over the ancient landscape and echoes of history weave through the hills. It was in this dramatic setting that a remarkable railway line was born, initially constructed to support the bustling mining activities in the region. The journey began in 1878 at Port Augusta, cutting through the stunning Pichi Richi Pass, with its grand opening at Quorn in 1879, and finally reaching its first terminus at Government Gums—now known as Farina—in 1882.

But that was just the beginning! The line swiftly extended its reach, connecting to Marree (then called Hergott Springs) in 1884 and Oodnadatta by 1891. With dreams of becoming a north-south transcontinental artery, it proudly adopted the name Great Northern Railway in 1882. Fast forward to 1926, and the Commonwealth Railways took over, rebranding it as the Central Australia Railway—a name that may lack flair but carries a legacy of resilience.

This 1225-kilometre (761-mile) marvel, which stretched to Stuart (renamed Alice Springs in 1930), became much more than just a railway; it was a lifeline for isolated outback communities. During World War II, it proved invaluable for transporting essential supplies, while also playing host to the iconic passenger train, The Ghan—a journey that has captured the hearts of countless travellers.

As the years passed, the Pichi Richi section transformed into a vital feeder route for the east-west Trans-Australian Railway from 1917 to 1937. Its steep gradients posed a significant challenge, largely due to the refusal of decision-makers (politicians and public servants) to heed the advice of surveyors and engineers. Instead of opting for a more straightforward path west of the Flinders Ranges, they prioritised servicing prospective copper mines and the anticipated agricultural riches of the area.

What was once a headache in operational terms has now evolved into a delightful escapade for modern travellers. Today, passengers aboard the trains marvel as powerful locomotives work tirelessly to conquer the daunting grades, transforming the arduous task into a thrilling experience that celebrates the line’s storied past. The railway, once a commercial venture, has turned into a nostalgic journey where history meets adventure in the captivating outback of Australia.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, August 16). Pichi Richi Railway. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pichi_Richi_Railway?oldformat=true

Hawker and the Flinders Ranges

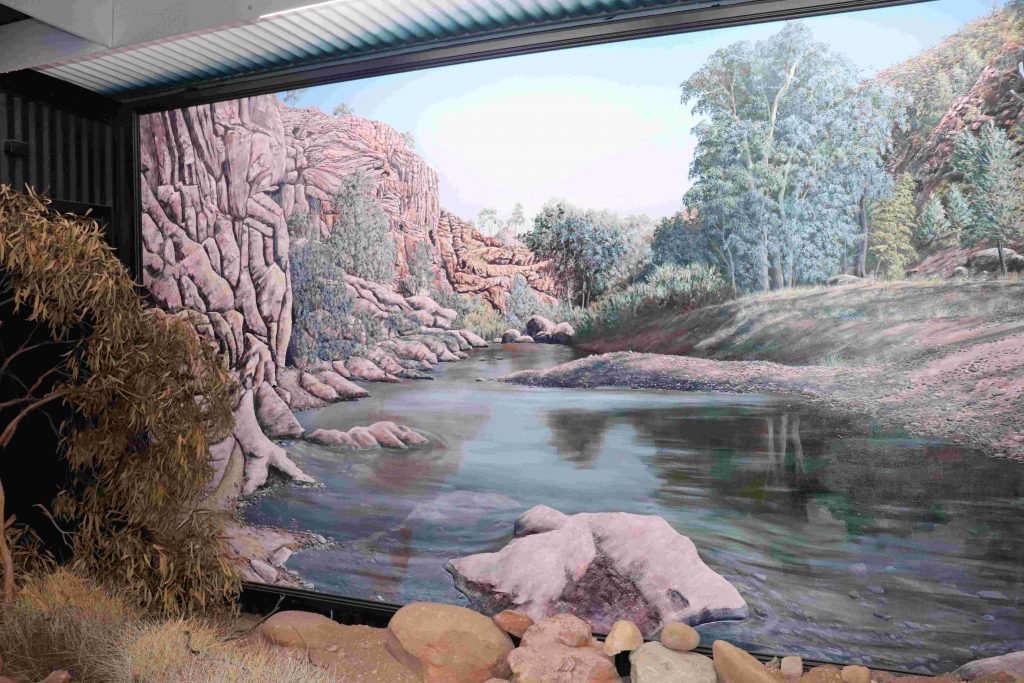

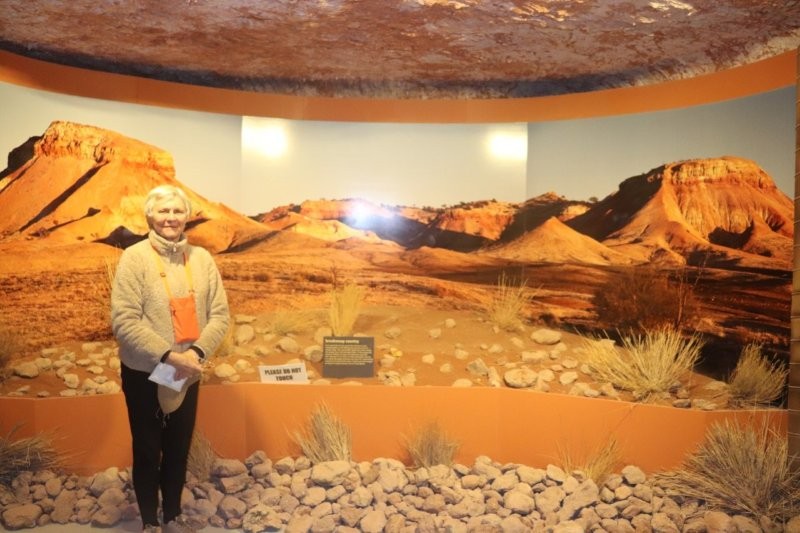

On our way to the Flinders Ranges, we stopped in Hawker to visit the Jeff Morgan Gallery—an unforgettable experience. This is a gobsmacking experience in the most unexpected place; 3D works of genius! Jeff Morgan so loved the Outback scenery that he re-created it in his gallery!

The exhibition proved to be an unforgettable adventure. The stunning displays are not just visual; they are immersive experiences of beauty that transport one to a vivid Outback. Every 3D Outback scape invited us to dive deeper into the beauty and unique wonder of the landscapes, prepared with great love and sensitivity.

Jeff was born in 1956 at Laura, a small country town at the southern end of the Flinders Ranges in South Australia. He grew up in nearby Wirrabara Forest where he attended the local primary school and then Gladstone High School showing a keen interest in, and a natural talent for, artwork.From the time he left school until 1990, Jeff did not draw or paint, but was busy working at the Wirrabara Woods and Forest Department and in his orchard. During this time he also married Miriam, brought up four sons, became a licensed painter-decorator and owned a hardware store in Laura. In 1990 Jeff experienced a change of direction and developed his skills as a fine artist.

Although Jeff did not receive any formal art training, he has studied by reading, visiting art galleries and observing the painting techniques of other artists. Jeff went on to become the Artist-in-Residence at Rawnsley Park in the Flinders Ranges for a period of three years. During this time Jeff’s natural ability to paint was further developed, often encouraged in his work by other artists who would visit to paint the Flinders Ranges. Jeff’s preferred painting medium is acrylics.

The rugged and dramatic scenery of the Australian outback and the Flinders Ranges continues to inspire Jeff to capture its beauty on canvas in his very unique and detailed style. Creating the Wilpena Panorama was a God-given vision, after having viewed a round panorama painting, the work of artist Henk Guth, in Alice Springs (since burnt down). It would be ten years before Jeff’s panorama building and painting were completed in 2003. With the creation of his panorama, Jeff has become one of a small number of panoramic artists in the world officially recognised by the International Panorama Council (IPC).

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, August 16). Pichi Richi Railway. Wikipedia.

Kanayaka

After visiting Hawker, we set off to Kanyaka Station.

A weird, strangely ghostly feeling pervades Kanayaka. When we arrived, Paul gave us his version of the events concerning Kanayaka. Apparently, the colonial government thought that sheep farming in the area would be a brilliant idea. Hugh Proby set off with 53000 sheep from Adelaide, trekking all the way to Kanayaka. When he got there—with an entourage of people with a wide range of skills—they set up a sheep station with all the infrastructure needed to develop the entire region into a booming sheep farming hub.

It was not to be.

The rains came in the first year or two, until the heavens dried up. South Australia, and more intensely, the Kanayaka area, was caught in a ten-year drought; this was probably the cycle of events that extended all the way back to Dreamtime! The local Aboriginal people were sanguine about it.

Proby was not that sanguine as he gazed over the remaining 4000 scraggly sheep chewing on the grey, dry salt bush. The poor sheep probably died of thirst quite quickly, as saline-free water is needed to stay alive!

When the rains eventually came, Hugh Proby had given up hope and was preparing to go back ‘home’, when he— most unfortunately— was swept away by a raging river that appeared from nowhere, and he drowned.

Here is the official course of events from Wikipedia—a bit different from the story we heard on the bus!

The area was inhabited by Aboriginal people for thousands of years before European settlement. The traditional owners of the area are the Barnggarla people.. The name of the station is taken from the Aboriginal word thought to mean Place of stone.

Kanyaka Station was established as a cattle station in February 1852 by Hugh Proby. He was born on 9 April 1826 at Stamford in Lincolnshire, England, the third son of Admiral Granville Leveson Proby (the third Earl of Carysfort of Ireland) and Isabella Howard. He emigrated on the ship Wellington, which arrived on 30 May 1851 at Port Adelaide, South Australia.

On 30 August 1852, Proby drowned when he was swept from his horse crossing the swollen Willochra Creek while trying to herd a mob of cattle during a thunderstorm. Aged 24, he was buried the following day. Six years later in 1858 his grave was marked with an engraved slab shipped from Britain by his brothers and sisters; it was said to weigh one and a half tons and posed a significant challenge to transport it to the grave site. Letters from Hugh Proby to his family in England during 1851-52 in which he describes his pioneering days establishing Kanyaka, as well as his Mookra Range run (now Coonatto station), were published in 1987 in a book.

Proby’s Kanyaka and Mookra Range holdings were sold to Alexander Grant. He and his brother, Frederick, settled on the Mookra Range run, which they renamed Coonatto.

Under subsequent owners, and particularly under resident manager John Randall Phillips, Kanyaka station grew in size until it was one of the largest in the district, with 70 families living and working there. Because of the difficulties of transport, the station had to be self-sufficient and Kanyaka station grew to include a large homestead, cottages for workers, workshops, huts and sheds, mostly built from local stone due to limited supplies of workable local timber. The station switched from cattle to sheep, but had cows, pigs, and vegetable gardens to supply food for the residents. There was also a cemetery. Proby was not buried in the Kanyaka cemetery, as it had not yet been established at the time of his death.

Severe droughts resulted in massive losses of sheep and eventually the station was abandoned. Due to its stone construction, many of the buildings survive today as ruins and are a popular tourist attraction.

After visiting Jeff Morgan’s Wilpena panorama in Hawker, we arrived at our accommodation in time to see the sunset over the Flinders Ranges as kangaroos and wallabies came out to feed.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, May 23). Kanyaka Station. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanyaka_Station?oldformat=true

As we left, a solitary sheep emerged from the salt bushes. We wondered if this was one of the descendants of Proby’s flock?

Wilpena Pound and Rawnsley Park

On our way to Wilpena Pound, we were informed that our accommodation arrangements had changed due to the bitterly cold weather and strong winds that roared across the ‘Pound’. We headed to Rawnsley Park Station instead.

Rawnsley Park Station proved to be ideal for launching off north towards the Oodnadatta Track and Lake Eyre. The mountains in the ‘Pound’ became ochred and shadowy as we arrived. The last rays of the setting sun brought out the beautiful colours of the surrounding mountains—once as high as Mt Everest—according to Paul, but now at a more modest height, in keeping with the ancient valleys and low-lying areas! ChatGPT and Wikipedia do not endorse Paul’s facts about the height of the Flinders Range Mountains.

After settling into our cabins, we shook off the travel sickness caused by the swaying coach by heading off to the Big 4 Caravan Park nearby. We were accompanied by kangaroos and wallabies that came out to feed.

Wilpena Pound, also known by the Adnyamathanha name Ikara (meaning ‘meeting place’), is a massive natural amphitheatre located in the Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park. Formed from ancient seabed rocks that were squeezed and uplifted by tectonic forces, the ‘Pound’ is a 17 km by 8 km elliptical crown of rugged mountains with the highest summit being St Mary Peak. It is a significant cultural site for the local Aboriginal people and a popular destination for bushwalking, offering breathtaking views.

After breakfast, we drove to Wilpena Creek, framed by huge river red gums, in the mystical heart of the Flinders Ranges with stunning views of this increasingly arid land. We passed the Cazneaux Tree along the way. Paul just mentioned the tree in one of his monologues as he sped past. Australian explorer Dick Smith tells us much more.

The Cazneaux Tree is not only an iconic symbol of the Flinders Ranges but also of the Australian outback. The tree itself, in my opinion, is no more remarkable than the thousands of other river red gums in Australia. Yes, it stands relatively alone on a flat plain in front of Wilpena Pound. But it’s likely you wouldn’t even notice the tree driving along the nearby main road.

What makes the Cazneaux tree special then?

The meaning attributed to the tree by Australian photographer Harold Pierce Cazneaux is what makes the tree well-known. Cazneaux – the grandfather of Australian explorer Dick Smith – photographed the tree in 1937 and called his work ‘The Spirit of Endurance’ based on traits he felt epitomised the tree’s survival in the semi-arid climate. In 1941, Cazneaux reflected on what the tree meant to him as his most “Australian” photograph:

‘This giant gum tree stands in solitary grandeur on a lonely plateau in the arid Flinders Ranges, South Australia, grown up from a sapling through the years, and long before the shade from its giant limbs ever gave shelter from heat to white men. The passing of the years has left it scarred and marked by the elements – storm, fire, water – unconquered, it speaks to us from a Spirit of Endurance.

Although aged, its widespread limbs speak of a vitality that will carry on for many more years. One day, when the sun shone hot and strong, I stood before this giant in silent wonder and admiration. The hot wind stirred its leafy boughs, and some of the living elements of this tree passed to me in understanding and friendliness expressing The Spirit of Australia. Dick Smith was heavily influenced by his grandfather.

How old is the Cazneaux tree? No one knows how long the Cazneaux tree has been standing stoically on that desolate plain, but river red gums can live for many centuries and potentially up to 1000 years. I think it’s good not to know how old the tree is because it simply adds to the mystery and romanticism of its legend. In any case, the Cazneaux tree is listed as significant by the National Trust with a diameter of 11.4 metres at the base and a height of 30 metres. Impressive, to say the least. The tree looks a little more geriatric today than it did in 1937. Many of the upper limbs are now devoid of leaves, with new growth on the trunk instead.

Brachina Gorge

Continuing our journey through Brachina Gorge, Paul seemed to be galvanised into ‘tour guide’ mode, and he gave us a very good account of the priceless geological treasures, crystal-clear waterholes, and the abundance of flora and fauna. Paul had saved this discourse all along, including a few excellent Outback yarns which he threw in for good measure.

Brachina Gorge stands as a testament to the Earth’s ancient history, which Paul laconically threw in our direction. As we drove through this striking natural feature, we followed a dry riverbed flanked by enormous cliffs that changed colour around nearly every turn.

We travelled down time, long past the time of the Roman Empire, going back to the beginning of time. We learned that Brachina Gorge holds one of the most complete records of sedimentary deposition in the world. On the Brachina Gorge Geological Trail, you pass rocks ranging from 650 million years to 520 million years old in a space of half an hour or so, over a distance of 20 kilometres. It’s hard to get your head around such a long period of time!

We passed dry riverbeds with gums pitched in a valiant battle for survival.

We saw Yellow-footed Rock-wallabies (a threatened species) found only in the gorge. These wallabies are distinguished by their bright yellow limbs and tail, hidden in the rugged, rocky terrain.

After lunch, we head to Parachilna before travelling into the desert country up the Oodnadatta Track. The cold weather persisted. Cold winds that set teeth chattering.

Mijneer Elferink

Paul took us to see Mr Cornelius Elferink, a ‘Sovereign State Citizen’—somewhere along the Oodnadatta Track.

‘Sovereign state believers’ refers to sovereign citizens, individuals who hold an anti-government, conspiratorial ideology that the law does not apply to them. They believe government is illegitimate and often disengage from societal structures like taxes, driver’s licenses, and other laws by using complex, false legal theories or “pseudolaw” to justify their actions. While some may act in isolation, the movement has seen growth, especially since 2020, and a small number of adherents have turned violent, leading to significant harm in communities and court systems.

Citation: Wikipedia contributors. (2025, November 1). Sovereign citizen movement. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sovereign_citizen_movement?oldformat=true.

Cornelius was innocuous and entirely self-sufficient and living on an isolated piece of land, on land so arid and a location so desolate that most would think that the only living thing there would be the chooks that scratched around in the pebbly soil among the salt bushes and the pig that has his/her snout in the dirtiest, muddiest little dam imaginable.

But Cornelius’s presence was everywhere—advertising boards in his front garden that explained his worldview and information that espoused his geographical and philosophical viewpoints—a mix of European, Aboriginal and colonial Australian culture. Yet, Cornelius was not crazy; he was an extreme, far-gone eccentric—and entirely self-sufficient. He told me that he had worked as an engineer in Western Australia. When asked if he was related to the Elferinks in Enschede, who I knew of, in the Netherlands, he replied in good Aussie slang, ‘Yeh Mate! That is possible’, as he stared in a north-westerly direction towards Europe, waving away the swarm of flies encircling his face.

That is when I saw Dedrie trying out Mr Elferi nk’s pedal washing machine.

Paul had warned us not to engage in philosophy, religion or politics with him, as this could condemn us to a monologue that lasted for many hours. I fell into the trap, tried to tap into Mr Elferink’s knowledge of Zen, but had to extricate myself from Paul’s clutches to make it onto the departing tourist bus.

We were on the way to Farina.

Farina— Ghost Town

On the way to Farina, we had lunch—it was still bitterly cold. Could barely hold the sandwiches and bananas; my hands were shaking so badly. Dedrie managed to retain some semblance of warmth, but still managed to look like the ‘Spy Who Came in from the Cold!

The ablution block toilet door would not close and kept swinging open, exposing me to the cold wind and any inquisitive passerby. I had grown immune to surprises by that time.

Ochre Cliffs

We followed the old Ghan railway line and arrived at Lyndhurst to explore the ochre cliffs.

We headed west on the dirt road for a couple of kilometres to reach the quarry lookout. From there, we saw a spectacular palette of rich earth colours of brown, red, orange, yellow and white. The cliffs are made of ochre—an earthy pigment containing ferric oxide, mixed with clay. The higher the iron oxide, the redder the ochre.

These cliffs of colour tell a story that began with time itself, and they are an important part of the culture of the first people to occupy this land, the Yantruwanta. The extensive ochre diggings extend over a square kilometre.

Ochre pits have been used by Aboriginal people for thousands of years. They traded the ochre with other tribes by foot over vast distances and in every direction of the continent. Ochre was an extremely valuable and spiritual item and played an important role in the continent’s economy.

Weekend Post adelaide

Research currently underway by the South Australian Museum is revealing that ochre has its own traces of geological DNA. Science and the latest technology are able to pinpoint with great accuracy the home location of the ochre. In modern times, ochre is used to depict Dreamtime stories through song and dance with some artists blending it with acrylic paints to create their iconic dot paintings.

Farina

The South Australian outback has its fair share of abandoned ghost towns. Farina is one such town. We turned off the asphalt—we were still travelling on a decent road—dreading the Oodnadatta Track, where we were told that we need to travel at speed to glide over the corrugations and avoid the dreaded sand. Once bogged, twice shy!

Then we entered Farina. Several tourists were driving along the dirt roads, walking along deserted roads and poking their heads into windowless buildings.

Dedrie and I decided to wander off and visit the cemetery, where Paul said there was an eerie, haunted atmosphere. We wandered around, tramping through broken beer bottle mounds around the pub and some of the abandoned buildings, looking for those sinister graves. They were nowhere to be found as we walked through the abandoned buildings. It was obvious that drinking was the a priori ‘cultural activity’ in the town. There were surprises everywhere. I vividly imagined that the wind howling through the deserted post office masked the chatter between the post master and one of the farmers lolling over the counter—ghosts in broad daylight?

As we wandered down one of the side streets, a willy-nilly swept past us, exposing more jagged pieces of broken bottles. I looked into a hole in the wall—once was a window—hoping to see the ghost of a cameleer, with camel—but to no avail.

We were jolted out of our reveries when we heard Paul’s petulant shout, ‘Jim! Dedrie! We’re leaving without you. Get on the bloody bus!’ The prospect of meeting up with some of the ghosts after dark certainly did not appeal!

In 1876, after a police trooper had been posted to the Government Gums, a ‘long neglected district’, a deputation asked for a portion of the district to be allotted as a township so that a post office might be erected; that a telegraph station be opened; and that a weekly mail service from Beltana to the north-west be set up. The townsite, on a reserve surrounding Gums Waterhole, was surveyed and on 21 March 1878, Farina Town was proclaimed.

Originally called The Gums or Government Gums, Farina was settled in 1878 by optimistic farmers hoping that rain follows the plough. The town became a railhead in 1882, but the railway was extended to Marree in 1884. During the wet years of the 1880s, plans were laid out for a town with 432 quarter-acre (0.10 hectares) blocks. It was believed that the area would be good for growing wheat and barley, but normal rainfall proved to be nowhere near enough for that. Several silver and copper mines were opened in the surrounding area.

Farina grew to reach a peak population of about 600 in the late 19th century. In its heyday, the town had two hotels (the Transcontinental and the Exchange), an underground bakery, a bank, two breweries, a general store, an Anglican church, five blacksmiths, a school (1879–1957) and a brothel. In 1909, a 1,143-kilogram iron meteorite was discovered north-east of the town.Wikipedia contributors. (2025, August 16). Farina, South Australia. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farina,_South_Australia?oldformat=true

Today, little remains of the township, except for stone ruins, a seasonally operating underground bakery, and the elevated water tank of the former railway. The post office closed in the 1960s. The 1067 mm narrow-gauge Central Australia Railway closed in 1958.

Marree

We rolled into Marree in the late afternoon, a charming little town right where the Birdsville and Oodnadatta Tracks meet. It’s a place with a fascinating history, still inhabited by the descendants of Afghan cameleers who once played a big role in its story. Marree was a bustling staging post for those large camel trains hauling goods back in the day, and it really gives you a sense of the adventure that took place here.

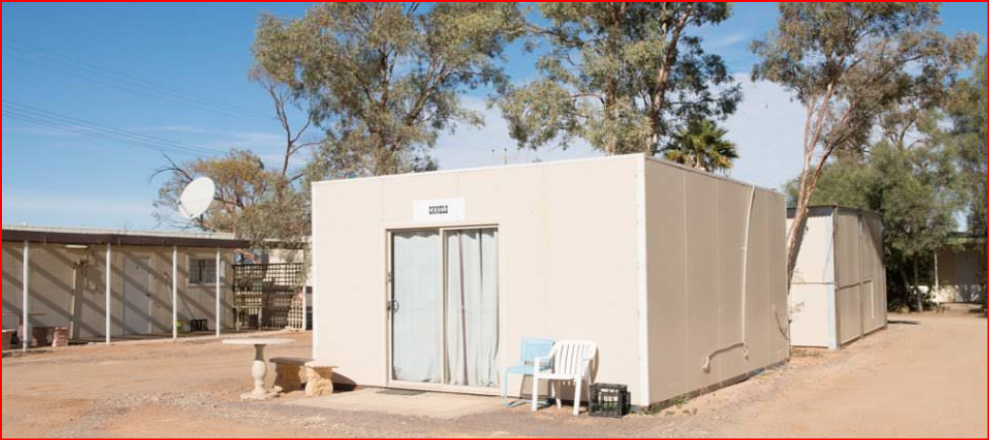

As Paul pulled up to the ‘Marree Cabins’, our first thoughts were that we had arrived at the local construction camp and that Paul had parked outside the local ablution block with outdoor dunnies! Our city sensibilities kicked in.

We were dead tired. Our jokes and bantering became serious as we milled around Paul to receive the keys to the little demountables; that’s what they were, we decided! We dragged our luggage to our cabin and unlocked the door to the strains of 1950s and 1960s music from the adjacent caravan park. The music was loud and seemed louder when we threw our cases onto the threadbare blankets on the small bed next to our main bed.

It was stuffy in the room. We discovered to our dismay that there were no windows in the room. The bitter cold had followed us all the way from Adelaide, and an ice-cold wind blew in through the huge gap in an ill-fitting entrance door. ‘We’re gonna get fuckin’ cold here, ‘ Dedrie said. ‘We’ll grab the blankets off the small bed, ‘ I optimistically said.

Just before 7 pm, Dedrie encouraged me to find my way to the local eatery, located within the local trading store. I made my way past screeching galahs and managed to get a good shot of them settling in for the night in a tree in one of the few houses next to the defunct railway station. I took some photos of the galahs, the local art on the dam wall, and the camel imaginatively constructed of steel wheels, strips of steel, springs, piping and drums.

The camel wagon was either a fabulous work of art or a derelict wagon awaiting removal by the local council. I decided that on the balance of probabilities, the wagon was a work of art—possibly awaiting some final touches.

I made my way to the trading store cum restaurant, where our fellow tourists were all seated around a very large table. Everyone was helping themselves to a most delicious plate of soup with tasty slices of home-baked bread. I dished up for myself and Dedrie, expecting her to emerge through the door at any minute.

Then bowl after bowl of lamb, pork, beef, chicken, all sorts of veggies, fruit, various puddings, and ice cream were brought in. We queued and filled our plates to the brim. I dished up for both of us. Then the red and white wine bottles were uncorked and set on the table. Everyone tucked in with gusto. The aches and pains due to a full day’s travel on the ‘Track’ were forgotten. We were in the highest of spirits!

‘But, where is Dedrie? ‘someone asked me. I had been staring at the open door for about half an hour, hoping to see her walk through. Then, a full hour later, she suddenly appeared at the door and found her way to us, mouthing somewhat incoherently, ‘They thought I was Aboriginal and wanted to give me a job’.

The story she then told us had us rolling with laughter. ‘I went in the direction of the restaurant, as Paul directed us. Then I saw the hotel, festooned with lights and reverberating with music. Ah, so that’s where we’re eating tonight. It should be great with such a party going on!’

The next thing she told us could only occur in the Outback. ‘I entered the hotel and made my way to the pub counter through the tipsy mob. The bar was unattended. I slipped behind the counter, just as the bartender came out.’ ‘Hey, watcha doing here! You know it’s illegal to come in behind the bar!’, he said. The manager, hearing the bartender, came out, saw what was happening and said to me with a smile, “Ullo love, you looking fer a job?” I said, ‘No thanks! I’m looking for Gekko. Are they in here?’ The manager must have thought to himself, “What’s with the bitch?” He flashed me a warm smile and waved me in the direction of this place. Well, here I am; pour me a glass and load up!’

The most perplexing thing about Marree was that the railway gauges didn’t match. Yes, the train cannot cross this road to the next track, just where I stood—in the middle of the roadway between the mismatched railway lines. Several Galahs screeched and cackled in ear-wrenching sympathy with me from a tree nearby. All I could do was scratch my head incredulously.

I did some more research.

Maree Railway Station in South Australia’s north, went from being the change-of-gauge station on the line between Port Augusta and Alice Springs from 1957 to being superseded in 1981 by the alternative Tarcoola-Alice Springs line and completely cut off from rail imput from 1987. The diesel locomotives were recalled when the Maree line was one of Australia’s first to use them exclusively

https://adelaideaz.com/articles/

We left for the Lake Eyre basin after breakfast at the ‘store–cum–eatery’, after a torrid night in the demountable motel room. The music from the caravan park had blared forth from the moment we arrived until 2:0 am. Sleep was impossible for most of the ‘Gekkoites’. The worst came just after 2:0 am. All of a sudden, a dark symphony of car hooters galvanised the night, accompanied by the choir of people coming to pick up the partygoers. Sleep was done for the rest of the night!

Lake Eyre Basin

We drove into the Lake Eyre Basin on the Oodnadatta Track, towards Coward Springs. We drove through the Wabma Kadarbu Conservation Park and entered the Coward Springs Campground. We were in good spirits as we entered this oasis in the middle of the increasingly arid, deserted landscape.

Paul had slept soundly, surprised to hear about the cacophony of the night before. He described the park in great detail to us. He showed us the mound springs, unusual natural features where water seeps to the surface from the Great Artesian Basin—the vast underground reservoir of water. This was fascinating. I had studied the details about the basin in Geography in my matriculation year in South Africa, which I shared with those on the coach who wanted to hear.

Paul described how sand and minerals deposited to form the mounds that stood above the surrounding flat, salty landscape. It’s a pity that we did not see the lush green reeds and other plants that grow around the spring and its overflow, the tail; our schedule did not allow such a break. Paul completed his exposition of the mounds by describing how the permanent water supports a variety of life, including birds, fish and aquatic invertebrates – some of which are found only in these springs.

Maybe next time!

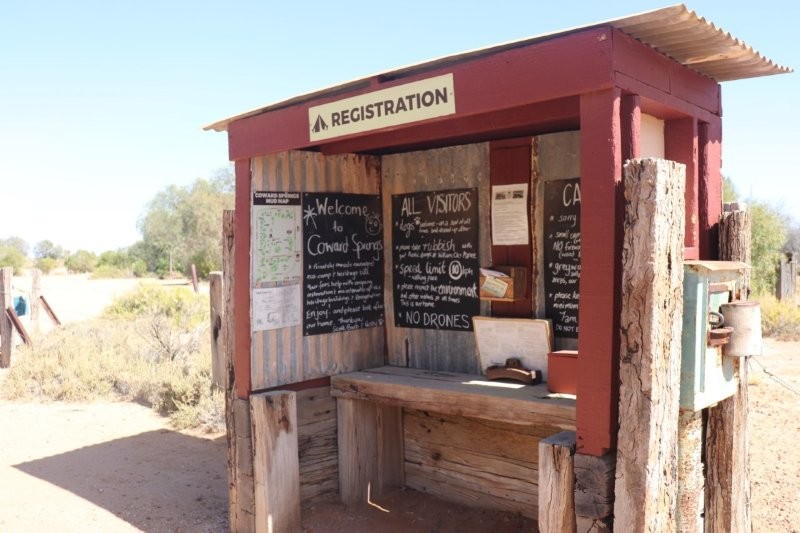

Coward Springs

Coward Springs Campground was once a station on the old Ghan railway line. The site was constructed in 1888 and abandoned before the line was closed in 1980. It is in the Middle of Wabma Kadarbu Mound Springs Conservation Park, and its admirable ethos is centred around conservation, with the three R’s: ‘reducing, recycling and reusing!’

We disembarked at the campground, nursing bruised and sore bottoms after we became airborne and then landed with a bump on the surface of the track. We savoured the freshly brewed coffee, farm fresh dates and some of the home-grown date products.

The new owners of the site, Scott and Barb, had upgraded the campsite, which included two houses, in-ground rainwater tanks, a bore, date palms and athel pines and the most interesting outback gardens, carefully and lovingly looked after. We enjoyed their hospitality, great coffees, fresh date scones; we would have liked to visit the rail museum about the original Ghan railway line, but Paul had a lot of driving to do to get us to Marree.

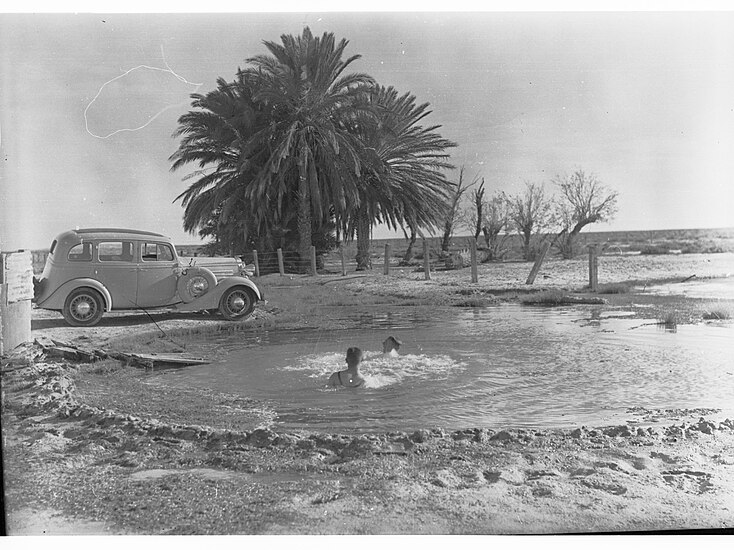

The South Australian government completed a 120 m borehole at the site in 1886 from which water from the Great Artesian Basin rose 4.6 m above ground. The salty water corroded the bore head and casing, flowing uncontrolled to form a large pool and, by the 1920s, a wetland in the dry gibber plain formed.

It was a popular place for local residents and, at a time when the railway’s outback timetables had room for delays, train crews and passengers had time for a swim.

In 1993, the South Australian government redrilled and relined the bore, reducing the flow rate. The campground operators subsequently built a ‘natural spa’ that mimicked the old pool, from which water was directed into the wetland. We did not have time to visit the spa—a pity!

The wetland is an oasis providing water and food, shelter and breeding areas for a wide range of wildlife. We saw many birds among the palms and heard them in the well-kept flower and shrub beds. Wikipedia tell us that the site hosts more than 99 plant species, 126 bird species and numerous small native mammals, reptiles, aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates.

Apparently a school was opened in 1888, but only lasted for two years. The Coward Springs Hotel, however, was licensed from 1887 to 1953. As trains pulled into the station, passengers were given directions to the ‘pub’ and the ‘bath’ for their choice of refreshment.

We headed north to Marree, deep into the Lake Eyre Basin. The track was unforgiving. Paul negotiated every corrugation and sandy bit with expert maneuvering: ‘That’s what 35 years of tourist guiding gives you—skills to tackle the Oodnadatta’, he said.

The countryside in the Lake Eyre Basin is primarily an arid and semi-arid landscape of dunes, rocky gibber plains, and floodplains, known as the Channel Country, which bursts into colour after infrequent rains. The area features iconic desert plants like spinifex and mulga, along with river red gums along watercourses, and becomes a temporary haven for waterbirds and other wildlife when rivers flood. We were fired up for the flight over the lake!

Lake Eyre

Lake Eyre is a stunning saltwater lake located in a desolate semi-desert region, covering an area of over 8,000 square kilometres. The lake fills with water only occasionally, a phenomenon that has occurred several times in the last three years. This happens when heavy rains sweep across Queensland, feeding the river systems that flow into the lake.

We drove from Coward Springs along the Oodnadatta Track towards William Creek, where we spent a delightful morning admiring the semi-desert flora and fauna, before we were to take a flight over the lake.

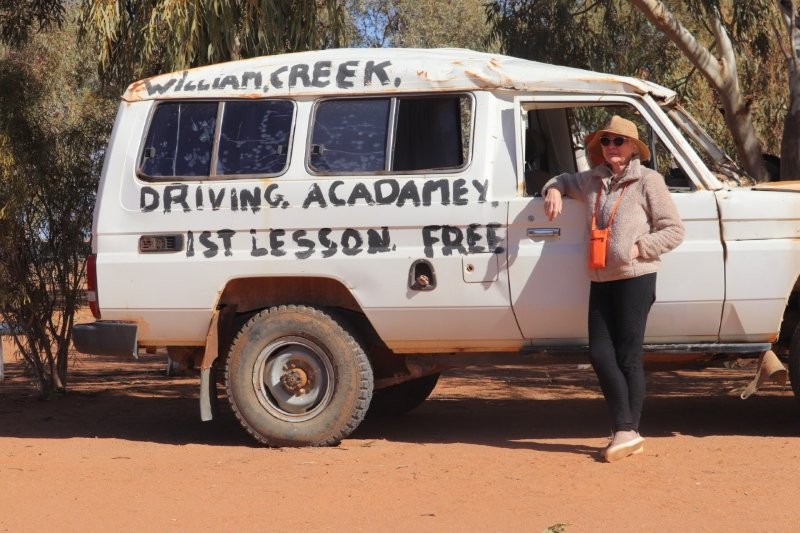

William Creek is a tiny town, found on the world’s largest cattle station. The 32,500-square-kilometre Anna Creek Station is Australia’s largest pastoral property. Located at the halfway point between Oodnadatta and Marree, the entire town is owned by Trevor Wright from Wrightsair and has its own power supply, as well as cabins and a caravan park.

We had a great lunch at the famous Williams Creek Hotel, built in 1887. The hotel is like a giant visitor’s book. Over the years it has been adorned with business cards and hand-scrawled notes. It’s also now the only solar-powered town in South Australia.

Before our flight, we spent some time viewing the outdoor museum with a small collection of rocket memorabilia from the Woomera Rocket Range.

William Creek Hotel is the kind of place where you never know who you’re going to meet or the stories you’ll swap.

As we went to lunch, we were pent up with excitement about the flight over the lake. We had all seen the various ABC programmes about the opulent avian life frequenting the lake after the inflow of water. We knew about the Pelicans that had travelled from far and wide, some 1000s of kilometres to be there; ‘They would feed on the delicious shrimps that inhabited the shores of the lake’, we were told. This was to be the pinnacle experience of our visit to the Outback!

Our excitement at the prospect of seeing this once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon could not be contained, as we waited to board the plane to skim the lake and descend to a few metres above ground level to savour the miraculous spectacle.

There were inveterate ‘twitchers’ in our group, armed with cameras and the appropriate bird-watchers’ telescopic lenses. ‘Oh, how marvellous that the ABC had brought this phenomenon to our attention!’, we all thought.

But Williams Creek has many delights, as the following images tell.

We set off to the William Creek airstrip, boasting a bitumen runway, which provides a smooth passage for scenic flights over Kati Thanda – Lake Eyre, the Painted Hills, and the most desolate of outback scenes.

We were there to experience significant historical events.

On the rare occasions that Lake Eyre fills completely (only three times between 1860 and 2025), it is the largest lake in Australia, covering an area of up to 9500 square kilometers.

Lake Eyre reached its peak flood in 2025, filling up to cover the entire lake by August 6, 2025, after floodwaters began arriving in early May. The floodwaters, sourced from Queensland, reached a major milestone with the Cooper Creek and Diamantina River systems. The peak passed on September 26, 2025, and the water receded due to evaporation. The Lake Eyre Yacht Club held its 25th Anniversary Regatta on the Cooper Creek in July 2025, as the floodwaters continued to flow towards the lake.

The Flight

In order to have an appreciation of our responses to the impending flight, let’s backtrack to the previous night in Marree.

After Dedries traumatic experience at the Marree Hotel, we made our way back to our cold, very cold cabin. As we opened the front door, we realised that the music from the adjacent caravan park, had become much louder—decibels louder. Dedrie went for a shower. Her shrieks and curses from the bathroom were telling. The shower water flow was intermittent; one minute the flow was luke warm, the next, freezing cold. Her misery was compounded by the cold wind blowing in from under the door.

We decided to go to bed immediately, the only way to keep warm. The threadbare blanket from the next bed was pulled over. I put in ear plugs and soon fell asleep, only to be woken by the thumping drumbeats and music from a 60s Beatles song, blaring even louder than earlier in the evening and punctuated by the blaring of horns. Dedrie muttered, ‘They’ve been going all night. Now the hooters have started up. I can hear people yelling’.

The music stopped. Car doors slammed and the night returned.

Back to the next day and the ‘Gekkoites’ boarding the plane.

The plane then took off with us all securely fastened after a detailed induction. The pilot was very knowledgable and answered all our questions good humouredly.

The pilot told us the full story after this disappointmnet, that ‘Birds at Lake Eyre primarily eat brine shrimp, especially the banded stilt. When the lake fills, native fish and aquatic invertebrates like brine shrimp become abundant, providing food for various birds like pelicans and Caspian terns’.

‘The Breakaways’

After disembarking from the ‘plane, we made our way back to the bus onto our next leg of the journey, travelling past the famous dingo fence and through the world’s largest cattle station, Anna Creek—on our way to ‘The Breakaways’ and then Coober Pedy.

We arrived at ‘The Breakaways’, a colourful land formation derived from the evaporation of an inland, ancient, Australian sea. The Breakaways are made up of a series of orange, white and red eroded hills rising over the desolate rocky plane. It is thought that the landscape of the Breakaways formed through the evaporation of an ancient inland sea, triggered by the continental shift that warmed the climate. The formations of the plateau would have been a chain of islands rising out of the ancient sea.

Paul became much more expansive as he described the ‘Two Dogs’ that appeared out of the desert—not actual dogs, but a landform known as Papa Kutjara , which consists of two joined hills—one brown and one white—formed by differing erosion rates.

These other worldly, strangely beautiful formations are part of a significant Aboriginal cultural landscape, with a nearby peaked hill representing the owner of the dogs, Wati. Beyond ‘Two Dogs’ lies Kalaya, the Emu, with her chicks represented by the white mounds at her feet.

Paul knew his geology. He told us, ‘The difference in color between the brown and white ‘dogs’ is due to different rates of weathering and erosion; the white hill has weathered faster than the brown hill.’

Park signage told us:

Welcome to Antakirinja Mutuntjarra Lands.

Park signage

This unique landform is known as papa or two dogs.

To the traditional aboriginal people it is two dogs sitting down – a grown one and a white one. It is a mens’ story.

To non-aboriginal people the landform is called the castle or salt pepper, simply because of the similarity to the colour and shape of the landform.

The difference in colouring of the two hills, although joined, has been caused by various stages of weathering and erosion.

The white hills has weathered faster then the brown hill.

Look to your right. You will see the peaked hill which is the wati, or man, who is the owner of the two dogs.

These landforms are examples of the breathtaking scenery forming the Breakaways Reserve. Please do not climb the landforms.

The Dog Fence

‘Just drive to the Dog Fence, take a left, and continue until the ground isn’t flat.’ These are the kinds of instructions that work in South Australia.

The Dog Fence itself is fascinating – a real marvel of scale that is only possible in a few places on the planet. It stretches for 5,600 kilometres across more than half of Australia. Made mainly of high wire mesh, it was first built in the 1880s and is still constantly maintained.

The aim is to keep dingoes out of the part of the country where most of the farmland is located.

Coober Pedy

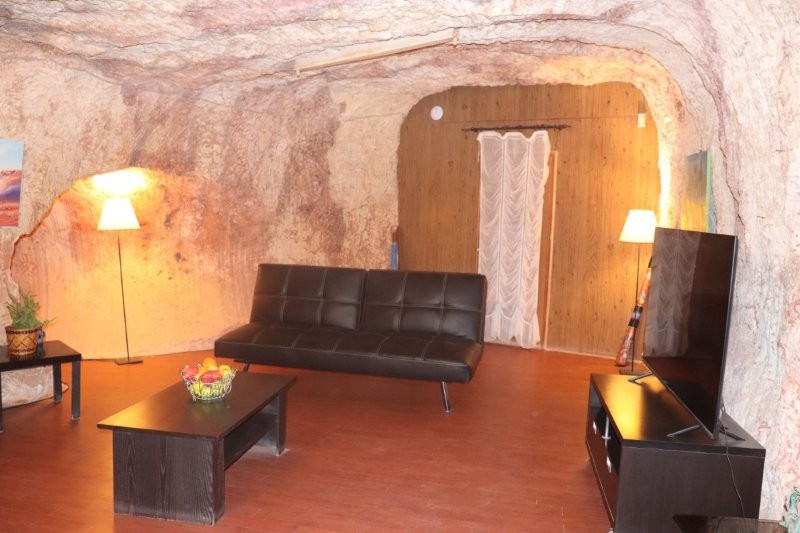

We travelled past the famous dingo fence and through the world’s largest cattle station, Anna Creek, before arriving in Coober Pedy, tired but amazed. Our accommodation was down in the innards of the earth, windowless, but into the labyrinth. The reception desk stood in an underground, carved-out room. Cool and fascinating.

We had to log on differently to get to wi-fi.

The next morning we had a guided tour explaining the history of Coober Pedy and watched a 20-minute award-winning documentary presented in an underground theatrette on three panoramic screens.

Coober Pedy, we learned, was founded in 1915 when a 14-year-old boy called William Hutchison discovered an opal. Initially named the Stuart Range Opal Field after the explorer John McDouall Stuart, the name Coober Pedy is thought to derive from the Aboriginal word kupa-piti.

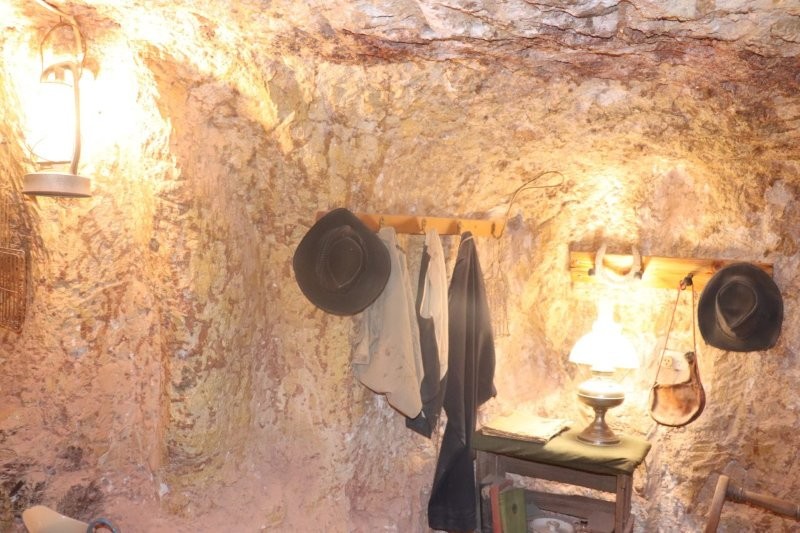

We learned about the opal industry, including an opal cutting demonstration. We then visited an underground dugout home and the Serbian underground church.

We visited Faye’s Underground Home, an iconic underground abode carved by Australia’s first female opal mine owner and industry trailblazer, Faye Nayler.

Such an underground home is unusual in most Aussie suburbs; it makes perfect sense to Coober Pedy residents, many of whom are accustomed to not only working in mines but living in cave-like dwellings to escape the sweltering desert temperatures. Faye, along with her two friends, painstakingly created the unique burrowed ‘dugout’ home, commencing the project in 1962.

Armed with nothing but picks, shovels and perseverance, the trio transformed the cave over ten years into a sprawling three-bedroom house – even carving out an indoor, underground swimming pool adjacent to the lounge area. As they built the property, the trio also continued to mine for precious gems on site. Their labour of love was completed in 1972 and quickly became a local icon.

So what’s it like inside? The interior of the home is a time capsule of retro outback style. The décor is frozen in the 60s and 70s, boasting stone walls, a vintage bar built from rocks, a lavish entertaining area, and of course that unmissable swimming pool.

We return to Coober Pedy for lunch via the dog fence and the moon plains.

We returned to Coober Pedy for lunch via the dog fence and the moon plains. Heading along the Stuart Highway, with tracts of desert scenery stretching out as far as the eye can see.

I thought I was back in Namaqualand and Bushmanland in South Africa as we drove to Woomera which was one of the world’s busiest launch sites for testing rockets and missiles during the 1950’s and 1960’s. O/n Eldo Hotel

Our sedate expression.

Woomera

Heading along the Stuart Highway, with tracts of desert scenery stretching out as far as the eye can see, we stopped at Glendambo and then arrived at Woomera which was one of the world’s busiest launch site for testing rockets and missiles during the 1950’s and 1960’s.

That night we stayed at the Eldo Hotel.

Woomera, unofficially Woomera village, is the domestic area of RAAF Base Woomera. Since 1947 it has been a Defence-owned and operated facility. The village is located on the traditional lands of the Kokatha people[1] in the Far North region[2] of South Australia, but is on Commonwealth-owned land and within the area designated as the Woomera Prohibited Area (WPA). The village is approximately 446 kilometres (277 mi) north of Adelaide. In common usage, “Woomera” refers to the wider RAAF Woomera Range Complex (WRC), a large Australian Defence Force aerospace and systems testing range (the Woomera Test Range (WTR)) covering an area of approximately 122,000 square kilometres (47,000 sq mi) and is operated by the Royal Australian Air Force.

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). View source for Woomera, South Australia – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Woomera%2C_South_Australia&action=edit&oldformat=true

The final leg of our journey was to Port Augusta.

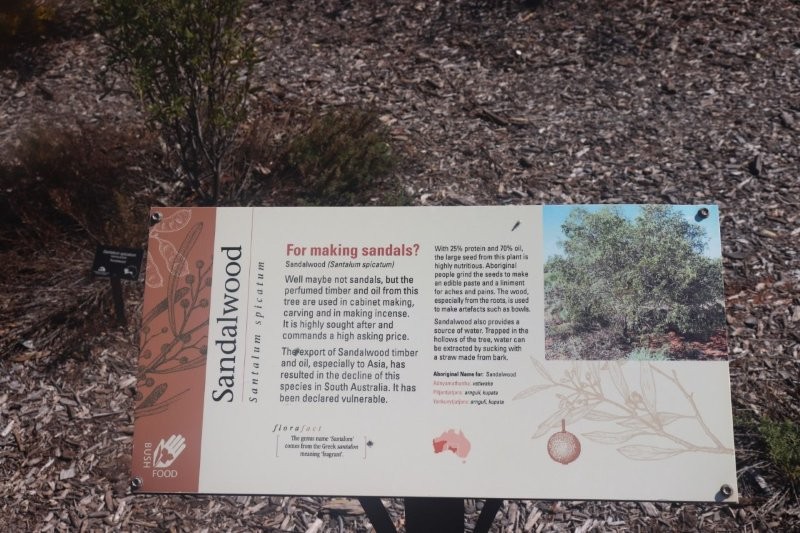

Arid Lands Botanical Garden

We departed from Woomera and headed towards Port Augusta, located along the serene waterways at the head of the Spencer Gulf. Upon our arrival, we enjoyed a delightful lunch followed by a remarkable tour of the Arid Lands Botanic Gardens. The Salt Bush Plains of the Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden present a fascinating ecosystem filled with hidden treasures. These expansive flat areas, characterised by low Saltbush vegetation, including Pearl and Black Bluebush, conceal populations of geckoes, fairy wrens, and some surprising life forms, such as fungi and extensive colonies of lichen.

The guide we had had extensive knowledge of this ecosystem and had us spellbound for a long time. She brought to life the absolutely stunning plants, birds, animals and insects that thrive in a picturesque setting of more than 250 hectares.

It felt like an entry to paradise, as the photographs clearly show. I had to rely on Google for information about the flora and fauna that our guide described. My memory from the late seventies brought back fragments of the knowledge she had shared. She was like a walking botanical encyclopedia!

Eucalypts

For Aboriginal peoples, the River Red Gum is deeply significant for providing physical sustenance, cultural practices, and spiritual connection to ‘Country’

The tree provides a vital source of food, medicine, and materials for tools and shelter, and its presence indicates the presence of water sources and fertile land.

The tree also holds stories of ancestral journeys. It serves as a symbol of strength and connection to the landscape, with historical evidence of cultural practices such as the scar trees, burial sites, and ceremonial places.

Spinifex

During our excursions from the coach on previous days, we had looked for signs of Spinifex everywhere, which Paul told us is rooted in Aboriginal culture and spirituality. Our search was in vain. We did not know what to look for! Our guide was quick to help us find the Spinifex in the garden and tell us the following.

She told us that Spinifex is prominent in Dreaming stories (Tjukurpa), passed down through art, oral traditions, and practices; one had to be careful not to touch the plant trustingly. One of our tour group members told us that Spinifex thorns had severely pricked both him and his granddaughter.

We took a step back as the tour guide explained: ‘Spinifex (Triodia) in Australia has extremely fine, sharp, grass-like spines that embed easily and are notoriously difficult to remove, causing intense pain, swelling, and often leading to persistent inflammation, granulomas (lumps), or even infections like tetanus, requiring careful removal with tweezers, sometimes after softening the skin, and seeking medical help for deep or infected pricks to prevent complications like plant thorn arthritis.

She told us that Spinifex is deeply embedded in Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime (Jukurrpa/Dreaming) stories, representing ancestral journeys, creation events, and crucial resources, particularly for the Spinifex People (Pila Nguru), whose art vividly depicts these sacred histories, linking the resilient desert grass to Country, spiritual identity, and traditional knowledge for architecture, medicine, and survival, especially in Central Australia. These stories explain the landscape, such as the formation of fairy circles by termites beneath spinifex, and are revitalised through contemporary art, connecting generations to their land and law.

Her rendition was mirrored by Google AI!

Hakea

Hakea has significant cultural importance for Aboriginal peoples, serving as a vital resource for food, water, medicine, and tools. Aboriginal people consumed the fruit flesh and nectar, used roots as a water source, and fashioned weapons, tools, and traps from the wood.

Some species also hold ceremonial value, with their seed pods used for decoration, and certain species’ flowers, like the Royal Hakea, have symbolic connections to warrior strength for groups like the Noongar-Wudjari.

The Hakea is a formidable predator in other countries.

Hakea species, especially Hakea sericea (silky hakea) and Hakea drupacea (sweet hakea), are major, highly invasive alien weeds in South Africa’s Western Cape, introduced from Australia for dune stabilisation and hedging but now choking out unique fynbos vegetation, increasing fire risk, and reducing water yield in mountain catchments. They form dense, impenetrable thickets that drastically alter landscapes and communities, requiring significant biological control efforts (like specific weevils and moths) and mechanical removal to manage their spread, with H. sericea classified as a Category 1b invasive species.

The Hakea species is central to the social and spiritual lives of Aboriginal people; it features in many cultural stories, offering an understanding of the living culture and knowledge systems of Aboriginal peoples. The Hakea forms part of the web of interrelationships between people and the natural environment.

I have glibly mentioned Aboriginal Spirituality without any discussion or definition. I have quoted some of the work of Vicki Grieves to help in the understanding of such spirituality. I see a strong correlation between the spirituality of Australian Aboriginal people and that of other Indigenous People in Africa and the Americas.

Vicki Grieves, (2009).Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy

‘The Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing’. Discussion Paper Series: No. 9CRCAH. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health. Discussion Paper Series – ISSN 1834–156X.

Aboriginal Spirituality:

Aboriginal Spirituality derives from a philosophy that establishes the wholistic notion of the interconnectedness of the elements of the earth and the universe, animate and inanimate, whereby people, the plants and animals, landforms and celestial bodies are interrelated.

These relations and the knowledge of how they are interconnected are expressed, and why it is important to keep all things in healthy interdependence is encoded, in sacred stories or myths. These creation stories describe the shaping and developing of the world as people know and experience it through the activities of powerful creator ancestors. These ancestors created order out of chaos, form out of formlessness, life out of lifelessness, and, as they did so, they established the ways in which all things should live in interconnectedness so as to maintain order and sustainability.

The creation ancestors thus laid down not only

the foundations of all life, but also what people had to do to maintain their part of this interdependence—the Law. The Law ensures that each person knows his or her connectedness and responsibilities for other people (their kin), for country (including watercourses, landforms, the species and the universe), and for their ongoing relationship with the ancestor spirits themselves.

Aboriginal people across Australia realise that the hard fruit of Hakea plants is a vital food source for the Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo and has spiritual meaning in Australia, featuring in stories about ‘Country’.

Bluebush, Saltbush & Others

The Pearl Bluebush has significant value as a food and medicinal source, with edible blueish seeds.

‘Has my research uncovered any spiritual or cultural references to the ‘Bluebush’? No, not at this stage—I am still looking!’

Wattles

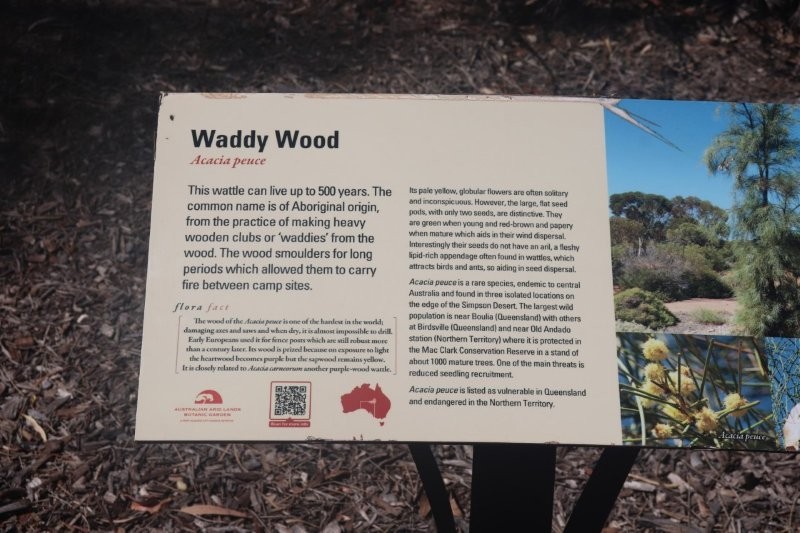

Indigenous Australians used the hard and heavy wood of the Waddy tree to produce clubs or waddy.

The tree is host to various butterflies and their larvae and also provides protective habitat for birds, such as grey falcons and desert finches. The foliage is often chewed by insects, but saplings are eaten by grazers, such as cattle and diprotodons. In the past, pastoralists used the tree to make highly durable and termite-resistant fenceposts and stockyards from the timber.

Waddy Wood

Wikipedia contributors. (2024, December 10). Acacia peuce. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acacia_peuce?oldformat=true

The Mulga tree offers healing through its resin and soothing qualities of its smoke. It is probably healthier than smoking anything else. The tree is more than just medicinal. It is intertwined with the cycles of seasons and various ceremonies, making it a cherished cultural symbol. Its presence shapes not only the landscapes but also the stories and connections within the Aboriginal community.

In many ways, the Mulga tree is a silent witness to the lives and traditions that surround it, and its significance is felt deeply by those who call this land ‘Country’.

An Australian Garden

Reminiscing

Amongst the dulling grey of an Australian autumn and winter there is an occasional burst of brilliant yellow in the bush landscape. These are the flowering wattles -no matter what time of year, a wattle will flower!

During a visit to the ‘Australian Garden” in Cranbourne, Victoria, I saw these beautiful yellow wattle flowers peeping out of the purple grey trees. The poem by Veronica Mason tells it all:

“The bush was grey

A week to-day

(Olive-green and brown and grey);

But now the spring has come this way,

With blossoms for the wattle.

It seems to be

A fairy tree;

It dances to a melody,

And sings a little song to me

(The graceful, swaying wattle):

See how it weaves

Its feathery sheaves:

Before the wind a maze it weaves,

A misty whirl of powdery leaves –

(The dainty, curtseying wattle):

Its boughs uplift

An elfin gift;

A spray of yellow, downy drift,

Through which the sunbeams shower and sift

Their gold-dust o’er the wattle.

The bush was grey

A week to-day

(olive-green and brown and grey);

But now its sunny all the way,

For, oh! the spring has come to stay,

With blossom for the wattle!

A plaque near these wattles in the Australian garden said that a key thing about the Australian landscape with the magnificent colours and forms of the flowers, grasses, trees, were the scents. Such aromaticity! Australian plants are said to be the most aromatic in the world. It is said that Diggers returning home after the 1st WW could smell the mainland whilst at sea!

Just as those Diggers were overjoyed to be coming home again, to the extent that they smelled the mainland, I again remembered the yellow blooms – in the old Transvaal where the wattles would bloom in spring. Those unpopular Australian dark grey wattles in the veld would be on fire – in a blaze of yellow, against the background of yellowing grass and the purple, blue, white cosmos along the sides of the road.

D H Lawrence wrote in his novel ‘Kangaroo’,

‘….in spring, the most delicate feathery yellow of plumes and plumes and plumes and trees and bushes of wattle, as if angels had flown right down out of the softest gold regions of heaven to settle here, in the Australian bush.’

The Wedding Bush has significance for marriage and commitment, as it was traditionally used in bridal bouquets and ceremonies in both Aboriginal and colonial culture, with its fragrant flowers exchanged during marriage rituals. The name itself comes from its historical use in Australian weddings.

The Blue Mallee flower has great medicinal properties and a source of water in arid areas. Aboriginal people historically used such plants for medicine, tool-making, and shelter, and in the arid Mallee regions, they knew how to obtain water from the roots.

This is not just an ordinary lizard! It is a diurnal (active in the daytime) reptile found across Eastern Australia—an Easter Bearded Dragon—it is a familiar part of the natural environment for Indigenous peoples. It is often seen in bushland and many urban areas.

While the Eastern Bearded Dragon is a real living creature and not a mythological figure, Aboriginal mythology does feature powerful, dragon-like ancestral creator beings known generally as Rainbow Serpents. These serpents are associated with waterholes, rain, and the shaping of the landscape, and their specific stories and names vary widely among different language groups across the continent. The animal is a natural part of the ecosystem and is treated with the general respect afforded to all native wildlife within Aboriginal cultures.

Of all the Eremophila species throughout Australia, Native Honeysuckle appears to be the most important and is still considered by the older generation Aboriginal people as the ‘number one medicine’. It is used both internally and externally, as a decongestant, expectorant and analgesic, and for inducing a feeling of general well-being.

Because this shrub was considered a general remedy, it was one of the few plants that the Aborigines often dried and stored, carrying the leaves with them in case of need. It is highly aromatic, fenchone being the major constituent of its essential oil fraction. The ailments reportedly cured by this shrub ranged from colds, influenza, headaches and fever, to relieving internal pain, cleansing septic wounds and encouraging deep sleep and pleasant dreams.

The broader term ‘mallee’ is considered to be of Aboriginal origin and is used to describe the multi-stemmed eucalyptus species common to arid and semi-arid regions.

The ‘Australian Native Castanet’ is the common name for Bursaria spinosa, also known as sweet or native blackthorn. It gets this name from its hard, castanet-shaped seed pods that can be used to make a rattling sound when shaken, but it is also sometimes called Castanet Bush. The colonials saw the castanets in the bush.

To Aboriginal people, a Castanet Bush probably features as an instrument in the great tapestry of plants that are part of ‘Country’. I suspect this, but I do not claim to fully understand it. This is what Aboriginal people say that they see:

Imagine a pattern. This pattern is stable, but not fixed. Think of it in as many dimensions as you like—but it has more than three. This pattern has many threads of many colours, and every thread is connected to, and has a relationship with, all of the others. The individual threads are every shape of life. Some—like human,

Kwaymullina, A. 2005, ‘Seeing the Light: Aboriginal law, learning and sustainable living in country’, Indigenous

kangaroo, paperbark—are known to western science as ‘alive’; others like rock, would be called ‘non-living’. But rock is there, just the same. Human is there too, though it is neither the most or the least important thread—it is one among many; equal with the others. The pattern made by the whole is in each thread, and all the threads

together make the whole. Stand close to the pattern and you can focus on a single thread; stand a little further back and you can see how that thread connects to others; stand further back still and you can see it all—and

it is only once you see it all that you can recognise the pattern of the whole in every individual thread. The whole is more than its parts, and the whole is in all its parts. This is the pattern that the ancestors made. It is life, creation spirit, and it exists in country (Kwaymullina 2005:13).

Law Bulletin, vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 12–15

Conebush is a general term that can refer to various native plants used by Aboriginal people for tools, food, and medicine. For example, its inner bark was used for making fishing lines and string, the wood for tools like spear throwers, and the seeds for food. Other plants are also commonly called conebush or have cone-like features and similar uses, such as Banksia, which was used for sweet drinks and as a water strainer.

Scarred Conebush are visual records of Aboriginal people’s use of the landscape over time, connecting them to their ancestors and past practices. Some trees are associated with important ceremonies, initiations, and other cultural practices.

The act of shedding bark can symbolise resilience and renewal, though this is not specific to corkbark but to the paperbark tree family more broadly. Aboriginal people removed bark from trees to make canoes, containers and shields.

Aboriginal People use the Corkbark Tree for building shelters and canoes, creating containers and shields, and for medicinal purposes. Trees with bark scars serve as markers of past human activity and cultural sites, providing valuable clues about the history of the people and the land.

Like most wattles, it is used as an antiseptic for cuts and abrasions, and the bark can be used to treat diarrhea, wounds, and inflammation. Some species were even used to treat headaches, skin ailments, and colds.

This wood is used to make spears and boomerangs, as well as tools and to provide shelter. The gum is used as a natural adhesive for binding materials together.

The flowering of this wattle, like other wattle species, signals seasonal changes, which guide Aboriginal communities in hunting and harvesting. Their seeds are in abundance during the ‘Malleefowl’ and ‘Bread’ Seasons

Wattle blooms symbolise new beginnings, growth, and spirituality. The plants also hold deep cultural significance, connecting people to Country and its resilience after fire.

Although hermaphroditic variations with bisexual flowers have been reported, this species is generally regarded as dioecious, with male and female flowers occurring on separate plants. The male flowers are at the ends of branches in disjunct beads, whereas the female flowers grow along panicles in dense clusters, typically around 20 cm in length.

The ‘Mallees’